8 Chapter Eight: Inchoate Offenses

Sections in Chapter 8

Introduction

Impossibility

Renunciation or Abandonment

Enforcement Powers, Enforcement Choices

Introduction

The previous three chapters have focused on different types of crime, but they share the same basic model of criminal liability: a statute defines conduct as criminal, and liability requires proof of (or the defendant’s admission to) all elements of the crime. This chapter and the next examine an array of doctrines that expand criminal liability to reach persons who plan, begin, encourage, or assist criminal activity without necessarily completing all elements of the target crime. These doctrines of expansion can be roughly divided into two categories, but there is some overlap between the two. First, the term inchoate offenses is often applied to crimes of beginning-but-not-finishing: persons who begin conduct designed to complete a crime, but then fail to complete all elements of the target crime, might be liable for an inchoate offense such as attempt [to commit x offense] or solicitation [to commit x offense]. For example, if I plan a bank robbery and drive to the bank with masks and guns, but then I am prevented from entering the building by savvy security guards, I may be liable for attempted bank robbery. Second, doctrines of group criminality, such as accomplice liability, allow persons to be convicted and punished based in part on the actions of other persons. If I provide support and encouragement to someone who commits bank robbery, accomplice liability could allow me to be convicted of the crime of bank robbery, even if I never set foot in a bank or took any money.

Again, there is some overlap between doctrines of inchoate offenses and doctrines of group criminality, and neither category is crisply defined. The term “conspiracy” can be especially confusing, since it is used to describe both an inchoate offense (e.g., conspiracy to distribute narcotics) and a doctrine of group criminality that allows one member of a conspiracy to be punished for offenses committed by another member of the conspiracy. This chapter focuses on the inchoate offenses of attempt and solicitation. Conspiracy in both senses just described will be addressed along with accomplice liability in the following chapter.

Like several of the offenses we have already studied, such as assault, murder, or burglary, the concept of a criminal attempt originated in common law courts but is today usually defined by statute. We will see two different kinds of attempt statutes in this chapter. Some attempt statutes refer to a specific type of criminal conduct. For example, the first case in this chapter concerns a prosecution under a statute that makes it a crime to attempt to commit a federal drug offense. But most American jurisdictions also have a general attempt statute that does not refer to any specific offense or category of offenses. A general attempt statute makes it a crime to attempt to commit any act designated as criminal elsewhere in the law. If a defendant is prosecuted under a general attempt statute, the prosecution will also need to identify which other offense—sometimes called “the target offense”—the defendant was attempting to commit. After the first case of this chapter, all the other cases involve prosecutions under general attempt statutes (in conjunction with the statutes that define the relevant target offense).

Attempt doctrine is thus usually “trans-substantive,” in that the general definition of an attempt can be paired with any type of criminal conduct. This chapter and the next do include several more cases on drug crimes, however, since inchoate offenses (and group criminality) are widely used in that context. But it is important to remember that a general attempt statute can be paired with almost any kind of offense. This chapter also includes one case involving attempted murder charges and one involving attempted distribution of pornography.

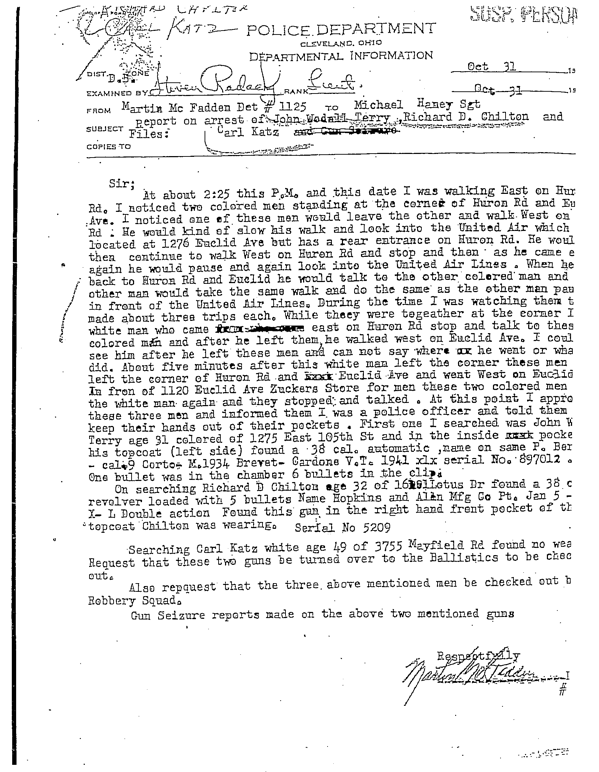

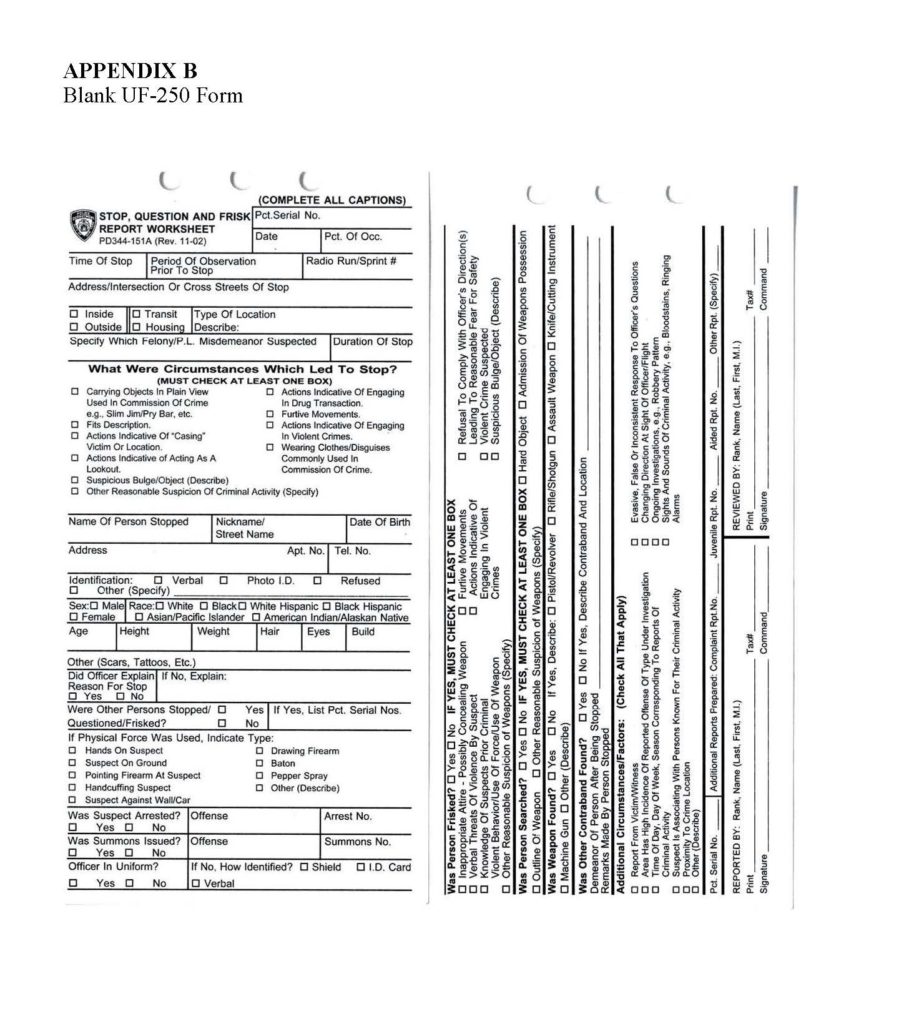

We have seen often the claim that a criminal conviction requires proof of all elements of an offense. Do inchoate offenses subvert that principle by allowing conviction for defendants who satisfy some but not all elements of the underlying offense? One recurring concern about inchoate crimes is the worry that this category of offenses are more or less “thought crimes”—the defendant is punished for intending to engage in some criminal act, even though he did not in fact engage in the specified conduct. In an effort to avoid punishing people for thoughts alone (and assuming we can discern and “prove” those thoughts), courts have struggled at length to define the kind of conduct that is sufficient to prove an attempt. How a jurisdiction defines a criminal attempt can depend upon why it is choosing to define attempts as criminal; this chapter will explore some possible rationales for punishing attempts and other inchoate offenses. As you consider those questions, it is also important to consider ways in which expansions of criminal liability increase the discretion of state officials. With discretion comes the possibility of discrimination. The role of inchoate offenses in producing racial disparities in convictions and imprisonment is an important but neglected topic for which there is relatively little empirical data available. But in this chapter and the next, look for ways in which efforts to expand criminal liability and enforcement authority have created opportunities for racialized enforcement.

This chapter should give you a basic understanding of the concept of a criminal attempt, both as that term was defined at common law and as it is now typically defined in contemporary statutes. The chapter also explores the separate inchoate offense of solicitation, which is basically the crime of asking someone else to commit a crime. You should also learn two principles that are invoked occasionally as limitations on attempt liability – impossibility and renunciation. Finally, attempt doctrine will give you a chance to revisit the interactions among criminalization choices, enforcement choices, and adjudication choices. The last section of this chapter offers a case study to help you apply attempt doctrine and review earlier material. This concluding section also offers a chance to explore further the questions raised in the previous paragraph: how are inchoate offenses and related expansions of criminal law connected to patterns of racial disparity in the American criminal legal system?

A. Preparation, Solicitation, Attempt

21 U.S.C. § 846. Attempt and conspiracy.

Any person who attempts or conspires to commit any offense defined in this subchapter [drug offenses] shall be subject to the same penalties as those prescribed for the offense, the commission of which was the object of the attempt or conspiracy.

UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff-Appellee

v.

Roy MANDUJANO, Defendant-Appellant

United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

499 F.2d 370

Aug. 19, 1974

RIVES, Circuit Judge:

Mandujano appeals from the judgment of conviction and fifteen-year sentence imposed by the district court, based upon the jury’s verdict finding him guilty of attempted distribution of heroin in violation of 21 U.S.C. § 846. We affirm.

I.

The government’s case rested almost entirely upon the testimony of Alfonso H. Cavalier, Jr., a San Antonio police officer assigned to the Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement. Agent Cavalier testified that, at the time the case arose, he was working in an undercover capacity and represented himself as a narcotics trafficker. At about 1:30 P.M. on the afternoon of March 29, 1973, pursuant to information Cavalier had received, he and a government informer went to the Tally-Ho Lounge, a bar located … in San Antonio. Once inside the bar, the informant introduced Cavalier to Roy Mandujano. …Mandujano asked the informant if he was looking for ‘stuff.’ Cavalier said, ‘Yes.’ Mandujano then questioned Cavalier about his involvement in narcotics. Cavalier answered Mandujano’s questions, and told Mandujano he was looking for an ounce sample of heroin to determine the quality of the material. Mandujano replied that he had good brown Mexican heroin for $650.00 an ounce, but that if Cavalier wanted any of it he would have to wait until later in the afternoon when the regular man made his deliveries. Cavalier said that he was from out of town and did not want to wait that long. Mandujano offered to locate another source, and made four telephone calls in an apparent effort to do so. The phone calls appeared to be unsuccessful, for Mandujano told Cavalier he wasn’t having any luck contacting anybody. Cavalier stated that he could not wait any longer. Then Mandujano said he had a good contact, a man who kept narcotics around his home, but that if he went to see this man, he would need the money ‘out front.’ To reassure Cavalier that he would not simply abscond with the money, Mandujano stated, ‘You are in my place of business. My wife is here. You can sit with my wife. I am not going to jeopardize her or my business for $650.00.’ Cavalier counted out $650.00 to Mandujano, and Mandujano left the premises of the Tally-Ho Lounge at about 3:30 P.M. About an hour later, he returned and explained that he had been unable to locate his contact. He gave back the $650.00 and told Cavalier he could still wait until the regular man came around. Cavalier [left], but arranged to call back at 6:00 P.M. When Cavalier called at 6:00 and again at 6:30, he was told that Mandujano was not available. Cavalier testified that he did not later attempt to contact Mandujano, because, ‘Based on the information that I had received, it would be unsafe for either my informant or myself to return to this area.’

II.

Section 846 of Title 21, entitled ‘Attempt and conspiracy,’ provides that,

“Any person who attempts or conspires to commit any offense defined in this subchapter is punishable by imprisonment or fine or both which may not exceed the maximum punishment prescribed for the offense, the commission of which was the object of the attempt or conspiracy.”

The theory of the government in this case is straightforward: Mandujano’s acts constituted an attempt to distribute heroin; actual distribution of heroin would violate 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1); therefore, Mandujano’s attempt to distribute heroin comes within the terms of § 846 as an attempt to commit an offense defined in the subchapter.

Footnote by the court: [Section 841(a)(1) provides:] ‘(a) Except as authorized by this subchapter, it shall be unlawful for any person knowingly or intentionally-

‘(1) to manufacture, distribute, or dispense, or possess with intent to manufacture, distribute, or dispense, a controlled substance.’

Under subsection 802(11) the term ‘distribute’ means ‘to deliver (other than by administering or dispensing) a controlled substance.’ Subsection 802(8) defines the terms ‘deliver’ or ‘delivery’ to mean ‘the actual, constructive or attempted transfer of a controlled substance, whether or not there exists an agency relationship.’

Mandujano urges that his conduct as described by agent Cavalier did not rise to the level of an attempt to distribute heroin…. He claims that at most he was attempting to acquire a controlled substance, not to distribute it; that it is impossible for a person to attempt to distribute heroin which he does not possess or control; that his acts were only preparation, as distinguished from an attempt; and that the evidence was insufficient to support the jury’s verdict. [There was a stipulation that no heroin had exchanged hands in this case.]

Apparently there is no legislative history indicating exactly what Congress meant when it used the word ‘attempt’ in § 846. There are two reported federal cases which discuss the question of what constitutes an attempt under this section. In United States v. Noreikis (7th Cir. 1973) … the court commented that,

‘While it seems to be well settled that mere preparation is not sufficient to constitute an attempt to commit a crime, it seems equally clear that the semantical distinction between preparation and attempt is one incapable of being formulated in a hard and fast rule. The procuring of the instrument of the crime might be preparation in one factual situation and not in another. The matter is sometimes equated with the commission of an overt act, the ‘doing something directly moving toward, and bringing him nearer, the crime he intends to commit.’

In United States v. Heng Awkak Roman (S.D.N.Y. 1973), where the defendants’ actions would have constituted possession of heroin with intent to distribute in violation of § 841 if federal agents had not substituted soap powder for the heroin involved in the case, the court held that the defendants’ acts were an attempt to possess with intent to distribute. The district court in its opinion acknowledged that … “there is no comprehensive statutory definition of attempt in federal law.” The court concluded, however, that it was not necessary in the circumstances of the case to deal with the “complex question of when conduct crosses the line between ‘mere preparation’ and ‘attempt.’”

The courts in many jurisdictions have tried to elaborate on the distinction between mere preparation and attempt….[1] In cases involving statutes other than § 846, the federal courts have confronted this issue on a number of occasions.

… United States v. De Bolt (S.D. Ohio 1918) involved an apparent attempt to sabotage the manufacture of war materials in violation of federal law. With regard to the elements of an attempt, the court in this case quoted Bishop’s New Crim. Law (1892) vol. 1, §§ 728, 729: “An attempt is an intent to do a particular criminal thing, with an act toward it falling short of the thing intended. Hence, the two elements of an evil intent and a simultaneous resulting act constitute, and yet only in combination, an indictable offense, the same as in any other crime.”

Gregg v. United States (8th Cir. 1940) involved in part a conviction for an attempt to import intoxicating liquor into Kansas. The court [noted] with apparent approval the definition of attempt urged by [the defendant]: “[A]n attempt is an endeavor to do an act carried beyond mere preparation, but falling short of execution, and that it must be a step in the direct movement towards the commission of the crime after preparations have been made. The act must ‘carry the project forward within dangerous proximity to the criminal end to be attained.’” The court held, however, that Gregg’s conduct went beyond ‘mere preparation’: “The transportation of goods into a state is essentially a continuing act not confined in its scope to the single instant of passage across a territorial boundary. In our view the appellant advanced beyond the stage of mere preparation when he loaded the liquor into his car and began his journey toward Kansas. From that moment he was engaged in an attempt to transport liquor into Kansas within the clear intent of the statute.”

…[In] United States v. Coplon (2nd Cir. 1950), where the defendant was arrested before passing to a citizen of a foreign nation classified government documents contained in [her] purse, Judge Learned Hand surveyed the law and addressed the issue of what would constitute an attempt:

“Because the arrest in this way interrupted the consummation of the crime one point upon the appeal is that her conduct still remained in the zone of ‘preparation,’ and that the evidence did not prove an ‘attempt.’ This argument it will be most convenient to answer at the outset. A neat doctrine by which to test when a person, intending to commit a crime which he fails to carry out, has ‘attempted’ to commit it, would be that he has done all that it is within his power to do, but has been prevented by intervention from outside; in short, that he has passed beyond any locus poenitentiae. Apparently that was the original notion, and may still be law in England; but it is certainly not now generally the law in the United States, for there are many decisions which hold that the accused has passed beyond ‘preparation,’ although he has been interrupted before he has taken the last of his intended steps. The decisions are too numerous to cite, and would not help much anyway, for there is, and obviously can be, no definite line; … There can be no doubt in the case at bar that ‘preparation’ had become ‘attempt.’ The jury were free to find that the packet was to be delivered that night, as soon as they both thought it safe to do so. To divide ‘attempt’ from ‘preparation’ by the very instant of consummation would be to revert to the old doctrine.”

… Although the foregoing cases give somewhat varying verbal formulations, careful examination reveals fundamental agreement about what conduct will constitute a criminal attempt. First, the defendant must have been acting with the kind of culpability otherwise required for the commission of the crime which he is charged with attempting. United States v. Quincy, 31 U.S. 445 (1832) (“The offenses consists principally in the intention with which the preparations were made…”)….

Second, the defendant must have engaged in conduct which constitutes a substantial step toward commission of the crime. A substantial step must be conduct strongly corroborative of the firmness of the defendant’s criminal intent. … The use of the word ‘conduct’ indicates that omission or possession, as well as positive acts, may in certain cases provide a basis for liability. The phrase ‘substantial step,’ rather than ‘overt act,’ is suggested by Gregg v. United States, supra (‘a step in the direct movement toward the commission of the crime’); United States v. Coplon, supra (‘before he has taken the last of his intended steps’) and [other cases] and indicates that the conduct must be more than remote preparation. The requirement that the conduct be strongly corroborative of the firmness of the defendant’s criminal intent also relates to the requirement that the conduct be more than ‘mere preparation,’ and is suggested by the Supreme Court’s emphasis upon ascertaining the intent of the defendant, United States v. Quincy, supra, and by the approach taken in United States v. Coplon, supra (‘. . . some preparation may amount to an attempt. It is a question of degree’).[2]

III.

The district court charged the jury in relevant part as follows:

[T]he essential elements required in order to prove or to establish the offense charged in the indictment, which is, again, that the defendant knowingly and intentionally attempted to distribute a controlled substance, must first be a specific intent to commit the crime, and next that the accused wilfully made the attempt, and that a direct but ineffectual overt act was done toward its commission, and that such overt act was knowingly and intentionally done in furtherance of the attempt.

‘* * * In determining whether or not such an act was done, it is necessary to distinguish between mere preparation on the one hand and the actual commencement of the doing of the criminal deed on the other. Mere preparation, which may consist of planning the offense or of devising, obtaining or arranging a means for its commission, is not sufficient to constitute an attempt, but the acts of a person who intends to commit a crime will constitute an attempt where they, themselves, clearly indicate a certain unambiguous intent to wilfully commit that specific crime and in themselves are an immediate step in the present execution of the criminal design, the progress of which would be completed unless interrupted by some circumstances not intended in the original design.

(Tr. Jury Trial Proc., pp. 138-139.) These instructions, to which the defendant did not object, are compatible with our view of what constitutes an attempt under § 846.

After the jury brought in a verdict of guilty, the trial court propounded a series of four questions to the jury:

‘(1) Do you find beyond a reasonable doubt that on the 29th day of March, 1973, Roy Mandujano, the defendant herein, knowingly, wilfully and intentionally placed several telephone calls in order to obtain a source of heroin in accordance with his negotiations with Officer Cavalier which were to result in the distribution of approximately one ounce of heroin from the defendant Roy Mandujano to Officer Cavalier?’

‘(2) Do you find beyond a reasonable doubt that the telephone calls inquired about in question no. (1) constituted overt acts in furtherance of the offense alleged in the indictment?’

‘(3) Do you find beyond a reasonable doubt that on the 29th day of March, 1973, Roy Mandujano, the defendant herein, knowingly, wilfully and intentionally requested and received prior payment in the amount of $650.00 for approximately one ounce of heroin that was to be distributed by the defendant Roy Mandujano to Officer Cavalier?’

‘(4) Do you find beyond a reasonable doubt that the request and receipt of a prior payment inquired about in question no. (3) constituted an overt act in furtherance of the offense alleged in the indictment?’

Neither the government nor the defendant objected to this novel procedure. After deliberating, the jury answered ‘No’ to question (1) and ‘Yes’ to questions (3) and (4). The jury’s answers indicate that its thinking was consistent with the charge of the trial court.

The evidence was sufficient to support a verdict of guilty… [T]he jury could have found that Mandujano was acting knowingly and intentionally and that he engaged in conduct—the request for and the receipt of the $650.00—which in fact constituted a substantial step toward distribution of heroin. From interrogatory (4), it is clear that the jury considered Mandujano’s request and receipt of the prior payment a substantial step toward the commission of the offense. Certainly, in the circumstances of this case, the jury could have found the transfer of money strongly corroborative of the firmness of Mandujano’s intent to complete the crime. Of course, proof that Mandujano’s ‘good contact’ actually existed, and had heroin for sale, would have further strengthened the government’s case; however, such proof was not essential.

Check Your Understanding (8-1)

Notes and questions on Mandujano

- What was Roy Mandujano’s sentence for the crime of attempted distribution of heroin? Look at the first sentence of the court’s opinion, and then at the penalty provisions of 21 U.S.C. § 846, the federal attempt statute. Though an attempted offense may seem “lesser” than a completed offense, many attempt statutes provide that an attempt can be punished with the same range of penalties available for the underlying offense. (See also note 1 after People v. Acosta later in this chapter.)

- Look again at 21 U.S.C. § 846, the federal attempt statute. It’s short! Notice that it uses the terms attempt and conspiracy, but does not define either term. This state was first enacted as part of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. The first two federal opinions to interpret section 846, both quoted in Mandujano, both noted that there was no precise definition of the term attempt in the statute, but each of these opinions also declined to provide a precise definition. Why might a court think that it is not necessary or desirable to define attempt, given the many different possible definitions listed in footnote 5?

- As the Mandujano court explains, at common law courts often emphasized that there was a difference between “mere preparation” to commit a crime, on one hand, and a legally punishable attempt, on the other hand. But judges struggled to explain what the difference was, and it’s not clear that there ever was a single common law definition of attempt. Instead, common law courts developed several different tests, the most important of which are listed in footnote 5 of the court’s opinion. Note that each definition refers to “the crime” or “the completed crime.” An attempt conviction is always based upon some other offense that is defined as criminal. That is, a defendant is not convicted of “attempt” in the abstract, but attempted murder, attempted theft, attempted distribution of heroin, and so on. Note also that the common law tests in footnote 5, and the discussions of attempt in earlier federal cases, define a general doctrine of attempt that is applicable to any offense. One recurring question is whether attempt can be meaningfully defined in this “transsubstantive” way—in other words, is the definition of attempt the same whether the target crime is murder or littering? Should it be the same? Or is the struggle to define attempt caused by the fact that courts want to define it differently depending on the underlying offense?

- Are there key differences between the various tests listed in footnote 5 of the Fifth Circuit opinion, or do these tests all amount to pretty much the same thing, as the court suggests? Would Roy Mandujano be guilty of attempted distribution of heroin under each common law definition of attempt?

- Ultimately, the Fifth Circuit adopts an understanding of attempt that follows the language of the Model Penal Code: the defendant must act “with the kind of culpability otherwise required for the commission of the crime,” and must also engage in conduct that constitutes a “substantial step” toward commission of the crime. Look closely at MPC § 5.01, quoted in footnote 6 of the court’s opinion and reprinted below. Notice that the “substantial step” is actually just one of three ways to commit an attempt. What are the other two?

- The Fifth Circuit did not quote the full text of MPC § 5.01, which offers several specific examples of the kind of conduct that can constitute a “substantial step.” The full text of MPC § 5.01 is reprinted below; it may be useful as we encounter other nuances of attempt law later in this chapter.

Model Penal Code § 5.01

(1) Definition of Attempt. A person is guilty of an attempt to commit a crime if, acting with the kind of culpability otherwise required for commission of the crime, he:

(a) purposely engages in conduct that would constitute the crime if the attendant circumstances were as he believes them to be; or

(b) when causing a particular result is an element of the crime, does or omits to do anything with the purpose of causing or with the belief that it will cause such result without further conduct on his part; or

(c) purposely does or omits to do anything that, under the circumstances as he believes them to be, is an act or omission constituting a substantial step in a course of conduct planned to culminate in his commission of the crime.

(2) Conduct That May Be Held Substantial Step Under Subsection (1)(c). Conduct shall not be held to constitute a substantial step under Subsection (1)(c) of this Section unless it is strongly corroborative of the actor’s criminal purpose. Without negativing the sufficiency of other conduct, the following, if strongly corroborative of the actor’s criminal purpose, shall not be held insufficient as a matter of law:

(a) lying in wait, searching for or following the contemplated victim of the crime;

(b) enticing or seeking to entice the contemplated victim of the crime to go to the place contemplated for its commission;

(c) reconnoitering the place contemplated for the commission of the crime;

(d) unlawful entry of a structure, vehicle or enclosure in which it is contemplated that the crime will be committed;

(e) possession of materials to be employed in the commission of the crime, that are specially designed for such unlawful use or that can serve no lawful purpose of the actor under the circumstances;

(f) possession, collection or fabrication of materials to be employed in the commission of the crime, at or near the place contemplated for its commission, if such possession, collection or fabrication serves no lawful purpose of the actor under the circumstances;

(g) soliciting an innocent agent to engage in conduct constituting an element of the crime.

(3) Conduct Designed to Aid Another in Commission of a Crime. A person who engages in conduct designed to aid another to commit a crime that would establish his complicity under Section 2.06 if the crime were committed by such other person, is guilty of an attempt to commit the crime, although the crime is not committed or attempted by such other person.

(4) Renunciation of Criminal Purpose. When the actor’s conduct would otherwise constitute an attempt under Subsection (1)(b) or (1)(c) of this Section, it is an affirmative defense that he abandoned his effort to commit the crime or otherwise prevented its commission, under circumstances manifesting a complete and voluntary renunciation of his criminal purpose. The establishment of such defense does not, however, affect the liability of an accomplice who did not join in such abandonment or prevention.

Within the meaning of this Article, renunciation of criminal purpose is not voluntary if it is motivated, in whole or in part, by circumstances, not present or apparent at the inception of the actor’s course of conduct, that increase the probability of detection or apprehension or that make more difficult the accomplishment of the criminal purpose. Renunciation is not complete if it is motivated by a decision to postpone the criminal conduct until a more advantageous time or to transfer the criminal effort to another but similar objective or victim.

- MPC § 5.01(1)(a) describes what are sometimes called “completed attempts,” or situations in which the defendant has the mental state required by the underlying crime and engages in all the conduct elements, but cannot be punished for the underlying crime itself because some attendant circumstance element cannot be established. For example, consider the facts of Heng Awkak Ranan, discussed in the Mandujano opinion.

- MPC § 5.01(1)(b) is similar to another common law explanation of attempt, the “last act” test. Under this test, a defendant was guilty of attempt if he had completed the “last act” or “last proximate act” necessary to accomplish the targeted crime. Most courts held that evidence of the last proximate act was sufficient but not necessary to prove attempt.

- What mental state must be “proven” (or admitted) in order to establish liability for attempt? The jury instructions used in Mandujano, quoted in the Fifth Circuit’s opinion, state that “a specific intent to commit the crime” is an element of attempt. This claim is somewhat at odds with the court’s reliance on the Model Penal Code, which avoided the common law terms “specific intent” and “general intent.” Those terms are notoriously ambiguous, as discussed in prior chapters. The claim that attempt requires specific intent is usually a claim that the defendant must have the purpose of accomplishing the underlying offense. Does the Model Penal Code require this particular mental state, or does it allow attempt liability even when the defendant does not think, “I want to commit x crime”? Look again at MPC § 5.01(1), above.

- These notes focus heavily on the Model Penal Code’s definition of attempt because Section 5.01 is one of the more influential portions of the MPC. A majority of U.S. jurisdictions now use the concept of a “substantial step” to define attempt, rather than one of the older common law tests. Whether this change in the words used to define attempt makes a difference, or what difference it makes, is a difficult question. Again, the Mandujano court treated all common law definitions of attempt as more or less equivalent, and treated “substantial step” as roughly equivalent to the common law. In People v. Acosta, presented later in this chapter, a New York court characterizes its common law dangerous proximity test as “apparently more stringent” than the substantial step test. But the dissent in Acosta observes that at the defendant’s trial, the jury was mistakenly instructed on the substantial step test rather than the dangerous proximity test—and no one objected!

- If redefining attempt along MPC lines does make a difference, how can we ascertain that difference? As noted in the next case in this chapter, the drafters of the MPC made clear that they intended the “substantial step” test to broaden the definition of attempt, making it possible to punish a greater range of preparatory actions. It is not clear whether lay jurors do or would actually interpret the language as the MPC drafters intended. One experimental study found that laypersons interpreted “substantial step” language more narrowly, not more broadly, than common law language such as “dangerous proximity.” Avani Mehta Sood, Attempted Justice: Misunderstandings and Bias in Psychological Constructions of Criminal Attempt, 71 Stan. L. Rev. 593 (2019). Sood’s study relied on experiments in which participants were asked to pretend to be jurors, not actual data from real prosecutions and convictions. In a world of guilty pleas, most convictions for attempted crimes are not based on jury deliberations at all. If legal professionals, including prosecutors and judges, believe that “substantial step” definitions of attempt reach more broadly than the common law tests, that belief could affect these professionals’ willingness to bring attempt charges or uphold attempt convictions.

- Professor Sood’s article also investigates ways in which decisionmakers’ cognitive biases might operate through attempt doctrine. Her experimental studies asked participants to evaluate the criminal responsibility of a Muslim defendant and a Christian defendant, each charged with an attempted offense. Participants were likely to judge the hypothetical Muslim defendant more harshly even when the fact scenario was written to suggest this defendant’s innocence. Professor Sood suggests that “lay constructions of criminal intent may inadvertently operate as a vehicle for discriminatory decisionmaking.” 71 Stan. L. Rev. at 654. Because we cannot “know” another person’s thoughts in the same sense that we can know (of) their actions, we inevitably rely on conjecture and guesswork when we attribute intentions to someone. In that process of attribution, cognitive biases appear to play a role. For this reason, several commentators have suggested that as criminal liability becomes more heavily based on judgments about intent, the more likely it is that racial bias will shape impositions of criminal liability. See, e.g., Luis Chiesa, The Model Penal Code, Mass Incarceration, and the Racialization of American Criminal Law, 25 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 605, 609 (2018) (critiquing the Model Penal Code’s definition of attempt for its emphasis on intention, and suggesting that the MPC has “made it easier for racial bigotry to slip through the seams of criminal law doctrine”).

Check Your Understanding (8-2)

South Dakota Codified Laws § 22-4-1. Attempt

Unless specific provision is made by law, any person who attempts to commit a crime and, in the attempt, does any act toward the commission of the crime, but fails or is prevented or intercepted in the perpetration of that crime, is punishable for such attempt at maximum sentence of one-half of the penalty prescribed for the underlying crime…

South Dakota Codified Laws § 22-16-4. Homicide as murder in the first degree

Homicide is murder in the first degree:

(1) If perpetrated without authority of law and with a premeditated design to effect the death of the person killed or of any other human being, including an unborn child; or

(2) If committed by a person engaged in the perpetration of, or attempt to perpetrate, any arson, rape, robbery, burglary, kidnapping, or unlawful throwing, placing, or discharging of a destructive device or explosive.

STATE of South Dakota, Plaintiff and Appellee

v.

Rocco William DISANTO, Defendant and Appellant

Supreme Court of South Dakota

688 N.W.2d 201

Decided Oct. 6, 2004

KONENKAMP, Justice.

… Defendant, Rocco William “Billy” Disanto, and Linda Olson lived together for two years and were engaged for a short time. But their turbulent relationship ended in January 2002. Olson soon began a new friendship with Denny Egemo, and in the next month, they moved in together. Obsessed with his loss, defendant began making threatening telephone calls to Olson and Egemo. He told them and others that he was going to kill them. He also sued Olson claiming that she was responsible for the disappearance of over $15,000 in a joint restaurant venture.

On February 17, 2002, while gambling and drinking at [a hotel], defendant told a woman that he intended “to shoot his ex-girlfriend, to kill her, to shoot her new lover in the balls so that he would have to live with the guilt, and then he was going to kill himself.” As if to confirm his intention, defendant grabbed the woman’s hand and placed it on a pistol in his jacket. The woman contacted a hotel security officer who in turn called the police. Defendant was arrested and a loaded .25 caliber pistol was taken from him.

In a plea bargain, defendant pleaded guilty to possession of a concealed pistol without a permit and admitted to a probation violation… While in the penitentiary [for these offenses], defendant met Stephen Rynders. He told Rynders of his intention to murder Olson and her boyfriend. Rynders gave this information to law enforcement and an investigation began. In June 2002, defendant was released from prison. Upon defendant’s release, Rynders, acting under law enforcement direction, picked defendant up and offered him a ride… At the suggestion of the investigators, Rynders told defendant that he should hire a contract killer who Rynders knew in Denver.

On the afternoon of June 11, 2002, Rynders and Dale McCabe, a law enforcement officer posing as a killer for hire from Denver, met twice with defendant. Much of their conversation was secretly recorded. Defendant showed McCabe several photos of Olson and gave him one, pointed out her vehicle, led him to the location of her home, and even pointed Olson out to him as she was leaving her home. In between his meetings with McCabe that afternoon, by chance, defendant ran into Olson on the street. Olson exclaimed, “I suppose you’re going to kill me.” “Like a dog,” defendant replied.

Shortly afterwards in their second meeting, defendant told McCabe, “I want her and him dead.” “Two shots in the head.” With only one shot, he said, “something can go wrong.” If Olson’s teenage daughter happened to be present, then defendant wanted her killed too: “If you gotta, you gotta, you know what I mean.” He wanted no witnesses. He suggested that the murders should appear to have happened during a robbery. Because defendant had no money to pay for the murders, he suggested that jewelry and other valuables in the home might be used as partial compensation. He told McCabe that the boyfriend, Egemo, was known to have a lot of cash. Defendant also agreed to pay for the killings with some methamphetamine he would later obtain.

At 3:00 p.m., defendant and McCabe appeared to close their agreement with the following exchange:

McCabe: So hey, just to make sure, no second thoughts or….

Defendant: No, none.

McCabe: You sure, man?

Defendant: None.

McCabe: Okay.

Defendant: None.

McCabe: The deal’s done, man.

Defendant: It’s a go.

McCabe: OK. Later. I’ll call you tonight.

Defendant: Huh?

McCabe: I’ll call you tonight.

Defendant: Thank you.

McCabe would later testify that as he understood their transaction, “the deal was sealed at that point” and the killings could be accomplished “from that time on until whenever I decided to complete the task.”

Less than three hours later, however, defendant, seeking to have a message given to McCabe, called Rynders telling him falsely that a “cop stopped by here” and that Olson had spotted McCabe’s car with its Colorado plates, that Olson had “called the cops,” that defendant was under intense supervision, and that now the police were alerted because of defendant’s threat against Olson on the street. All of this was untrue. Defendant’s alarm about police involvement was an apparent ruse to explain why he did not want to go through with the killings.

Defendant: So, I suggest we halt this. Let it cool down a little bit….

Rynders: Okay.

Defendant: So I don’t know if that house (Olson’s) is being watched, do you know what I’m saying?

Rynders: Okay.

Defendant: And, ah, the time is not right right now. I’m just telling you, I, I don’t feel it. I feel, you know what I mean. I’m not backing out of it, you know what I’m saying.

Rynders: Um hm.

Defendant: But, ah, the timing. You know what I mean. I just got out of prison, right?

Defendant: So, ah, I’m just telling you right now, put it on hold.

Rynders: Okay.

Defendant: And that’s the final word for the simple reason, ah, I don’t want nothing to happen to [McCabe], you know what I mean?

Defendant: Let it cool down. Plus let’s let ‘em make an offer …. [referring to defendant’s lawsuit against Olson]

Rynders: Well, I have no clue where [McCabe is] at right now.

Defendant: Oh, God. You got a cell number?

Defendant: Get it….

Defendant: I just don’t feel good about it to be honest and I’ll tell ‘ya, I’ve got great intuition.

Rynders: Okay.

Defendant: So, I mean, just let him [McCabe] know. Alright buddy?

Rynders: Okay.

Defendant: Get to him. He’s gonna call me at 11 tonight.

Despite this telephone call, the next day, McCabe, still posing as a contract killer, came to defendant at his place of employment with Olson’s diamond ring to verify that the murders had been accomplished. McCabe drove up to defendant and beckoned him to his car.

McCabe: Hey, man. Come here. Come here. Come here. Jump in, man. Jump in, dude.

Defendant: You sure?

McCabe: Jump in.

Defendant: I can’t, I can’t leave the bakery. I ain’t got the key.

McCabe: Fuck, I gotta get the fuck out of here, dude. It’s done, man. Fuckin’ done, dude.

Defendant: Okay. I don’t wanna know nothin’ about it.

McCabe: All right. Check this out, man. [Showing him Olson’s diamond ring.]

Defendant: No.

McCabe: Here.

Defendant: I don’t wanna see nothin’.

McCabe: I got that shit.

Defendant: Good.

McCabe: Hey. You still owe me some shit, man.

Defendant: Guaranteed.

Defendant was arrested and charged with three counts of attempted murder. He was also charged with one count of simple assault for the threat he made against Olson on the street….

A jury convicted defendant of all charges. He was sentenced to three concurrent thirty-year terms of imprisonment in the South Dakota State Penitentiary. In addition, he received a concurrent 365 days in jail. He was fifty-nine years old at the time. These sentences were consecutive to the unfinished two-year term defendant was to serve for his prior felony conviction. …

Defendant argues that the trial court erred in denying his motion for judgment of acquittal because the State failed to offer sufficient evidence to sustain a conviction on the three counts of attempted murder. …

In defining the crime of attempt, we begin with our statute, [which] states that “Any person who attempts to commit a crime and in the attempt does any act toward the commission of the crime, but fails or is prevented or intercepted in the perpetration thereof, is punishable” as therein provided. To prove an attempt, therefore, the prosecution must show that defendant (1) had the specific intent to commit the crime, (2) committed a direct act toward the commission of the intended crime, and (3) failed or was prevented or intercepted in the perpetration of the crime.

We need not linger on the question of intent. Plainly, the evidence established that defendant repeatedly expressed an intention to kill Olson and Egemo, as well as Olson’s daughter, if necessary. As McCabe told the jury, defendant “was a man on a mission to have three individuals murdered.”

Defendant does not claim error in any of the court’s instructions to the jury. The jury was instructed in part that

Mere preparation, which may consist of planning the offense or of devising, obtaining or arranging the means for its commission, is not sufficient to constitute an attempt; but acts of a person who intends to commit a crime will constitute an attempt when they themselves clearly indicate a certain, unambiguous intent to commit that specific crime, and in themselves are an immediate step in the present commission of the criminal design, the progress of which would be completed unless interrupted by some circumstances not intended in the original design. The attempt is the direct movement toward commission of the crime after the preparations are made.

Once a person has committed acts which constitute an attempt to commit a crime, that person cannot avoid responsibility by not proceeding further with the intent to commit the crime, either by reason of voluntarily abandoning the purpose or because of a fact which prevented or interfered with completing the crime.

However, if a person intends to commit a crime but before the commission [of] any act toward the ultimate commission of the crime, that person freely and voluntarily abandons the original intent and makes no effort to accomplish it, the crime of attempt has not been committed.

Defendant contends that he abandoned any attempt to murder when he telephoned Rynders to “halt” the killings. The State argued to the jury that defendant committed an act toward the commission of first degree murder by giving the “hit-man” a final order to kill, thus making the crime of attempt complete. If he went beyond planning to the actual commission of an act, the State asserted, then a later abandonment would not extricate him from responsibility for the crime of attempted murder. On the other hand, if he only wanted to postpone the crime, then, the State contended, his attempt was merely delayed, not abandoned.

On the question of abandonment, it is usually for the jury to decide whether an accused has already committed an act toward the commission of the murders. Once the requisite act has been committed, whether a defendant later wanted to abandon or delay the plan is irrelevant. As Justice Mosk of the California Supreme Court wrote,

It is obviously impossible to be certain that a person will not lose his resolve to commit the crime until he completes the last act necessary for its accomplishment. But the law of attempts would be largely without function if it could not be invoked until the trigger was pulled, the blow struck, or the money seized. If it is not clear from a suspect’s acts what he intends to do, an observer cannot reasonably conclude that a crime will be committed; but when the acts are such that any rational person would believe a crime is about to be consummated absent an intervening force, the attempt is under way, and a last-minute change of heart by the perpetrator should not be permitted to exonerate him.

People v. Dillon (Cal. 1983).

The more perplexing question here is whether there was evidence that, in fulfilling his murderous intent, defendant committed an “act” toward the commission of first degree murder. Defendant contends that he never went beyond mere preparation. In State v. Martinez, this Court declared that the boundary between preparation and attempt lies at the point where an act “unequivocally demonstrate[s] that a crime is about to be committed.” Thus, the term “act” “presupposes some direct act or movement in execution of the design, as distinguished from mere preparation, which leaves the intended assailant only in the condition to commence the first direct act toward consummation of his design.” The unequivocal act toward the commission of the offense must demonstrate that a crime is about to be committed unless frustrated by intervening circumstances. However, this act need not be the last possible act before actual accomplishment of the crime to constitute an attempt.

We have no decisions on point in South Dakota; therefore, we will examine similar cases in other jurisdictions. In murder for hire cases, the courts are divided on how to characterize the offense: is it a solicitation to murder or an act toward the commission of murder? Most courts “take the view that the mere act of solicitation does not constitute an attempt to commit the crime solicited…” …

A majority of courts reason that a solicitation to murder is not attempted murder because the completion of the crime requires an act by the one solicited. … In State v. Otto, 629 P.2d 646 (1981), the defendant hired an undercover police officer to kill another police officer investigating the disappearance of the defendant’s wife. A divided Idaho Supreme Court reversed the attempted first-degree murder conviction, ruling that the act of soliciting the agent to commit the actual crime, coupled with the payment of $250 and a promise of a larger sum after the crime had been completed, amounted to solicitation to murder rather than attempted murder. The court in Otto held that “[t]he solicit[ation] of another, assuming neither solicitor nor solicitee proximately acts toward the crime’s commission, cannot be held for an attempt. He does not by his incitement of another to criminal activity commit a dangerously proximate act of perpetration. The extension of attempt liability back to the solicitor destroys the distinction between preparation and perpetration.” In sum, “[n]either [the defendant in Otto] nor the agent ever took any steps of perpetration in dangerous proximity to the commission of the offense planned.”

Requisite to understanding the general rule “is the recognition that solicitation is in the nature of the incitement or encouragement of another to commit a crime in the future [and so] it is essentially preparatory to the commission of the targeted offense.” The Idaho Supreme Court made the rather pointed observation that “…jurisdictions faced with a general attempt statute and no means of severely punishing a solicitation to commit a felony might resort to the device of transforming the solicitor’s urgings into [an attempt,] but doing so violates the very essence of the requirement that a sufficient actus reus be proven before criminal liability will attach.”[3]

Cases like Davis [and] Otto … are helpful to our analysis because, at the time they were decided, the statutes or case law in those jurisdictions defined attempt in a way identical to our attempt statute. Under this formulation, there must be specific intent to commit the crime and also a direct act done towards its commission….

To understand the opposite point of view, we will examine cases following the minority rule. But before we begin, we must first consider the definition of attempt under the Model Penal Code, and distinguish cases decided under its formula. In response to court decisions that hiring another to commit murder did not constitute attempted murder, many jurisdictions created, sometimes at the urging of the courts, the offense of solicitation of murder. As an alternative, another widespread response was to adopt the definition of attempt under the Model Penal Code. This is because the Model Penal Code includes in criminal attempt much that was held to be preparation under former decisions. This is clear from the comments accompanying the definition of criminal attempt in Tentative Draft No. 10 (1960) of the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code, Article 5 § 5.01. The intent was to extend the criminality of attempts by drawing the line further away from the final act, so as to make the crime essentially one of criminal purpose implemented by a substantial step highly corroborative of such purpose. … The Model Penal Code treats the solicitation of “an innocent agent to engage in conduct constituting an element of the crime,” if strongly corroborative of the actor’s criminal purpose, as sufficient satisfaction of the substantial step requirement to support a conviction for criminal attempt.

… State v. Molasky (Mo. 1989) … is instructive. There, a conviction for attempted murder was reversed, but only because the conduct consisted solely of conversation, unaccompanied by affirmative acts. … [T]he court reasoned, “a substantial step is evidenced by actions, indicative of purpose, not mere conversation standing alone.” Acts evincing a defendant’s seriousness of purpose to commit murder, the Molasky Court suggested, might be money exchanging hands, concrete arrangements for payment, delivering a photograph of the intended victim, providing the address of the intended victim, furnishing a weapon, visiting the crime scene, waiting for the victim, or showing the hit man the victim’s expected route of travel. Therefore, under the relaxed standards of the Model Penal Code, evidence of an act in furtherance of the crime could include what defendant did here, provide a photograph of the intended victim and point out her home to the feigned killer. Molasky crystallizes our sense that without the expansive Model Penal Code definition of attempt, acts such as the ones defendant performed here are not sufficient under our definition to constitute attempt.

Knowing that the Model Penal Code relaxes the distinction between preparation and perpetration, we exclude from our analysis those murder for hire cases using some form of the Code’s definition of attempt. Obviously, we cannot engraft a piece of the Model Penal Code onto our statutory definition of attempt, for to do so would amount to a judicial rewriting of our statute. Nonetheless, there are several courts taking the minority position that solicitation of murder can constitute attempted murder, without reference to the Model Penal Code definition….

The minority view … is epitomized in the dissenting opinion in Otto, where it was noted that efforts to distinguish between “acts of preparation and acts of perpetration” are “highly artificial, since all acts leading up to the ultimate consummation of a crime are by their very nature preparatory.” For these courts, preparation and perpetration are seen merely as degrees on a continuum, and thus the distinction between preparation and perpetration becomes blurred.

In interpreting our law, all “criminal and penal provisions and all penal statutes are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect their objects and promote justice.” SDCL 22-1-1. Under our longstanding jurisprudence, preparation and perpetration are distinct concepts. Neither defendant nor the feigned “hit man” committed an act “which would end in accomplishment, but for … circumstances occurring … independent of[] the will of the defendant.”

We cannot convert solicitation into attempt because to do so is obviously contrary to what the Legislature had in mind when it set up the distinct categories of solicitation and attempt. Indeed, the Legislature has criminalized other types of solicitations. See SDCL 22-43-2 (soliciting commercial bribe); SDCL 22-23-8 (pimping as felony); … SDCL 22-22-24.5 (solicitation of minor for sex); SDCL 16-18-7 (solicitation by disbarred or suspended attorney).

Beyond any doubt, defendant’s behavior here was immoral and malevolent. But the question is whether his evil intent went beyond preparation into acts of perpetration. Acts of mere preparation in setting the groundwork for a crime do not amount to an attempt. Under South Dakota’s definition of attempt, solicitation alone cannot constitute an attempt to commit a crime. Attempt and solicitation are distinct offenses. To call solicitation an attempt is to do away with the necessary element of an overt act. Worse, to succumb to the understandable but misguided temptation to merge solicitation and attempt only muddles the two concepts and perverts the normal and beneficial development of the criminal law through incremental legislative corrections and improvements. It is for the Legislature to remedy this problem, and not for us through judicial expansion to uphold a conviction where no crime under South Dakota law was committed.

Reversed.

SABERS, Justice (concurring).

I agree because the evidence indicates that this blundering, broke, inept 59 year-old felon, just out of prison, was inadequate to pursue or execute this crime without the motivating encouragement of his “friend from prison” and law enforcement officers. On his own, it would have been no more than a thought.

GILBERTSON, Chief Justice (dissenting).

… [Defendant’s acts were] far more than mere verbal solicitation of a hit man to accomplish the murders….

… Defendant argues that the evidence clearly demonstrates that Defendant’s actions in June 2002 did not go beyond mere preparation. Defendant cites the police’s failure to arrest Defendant after the June 11, 2002 meeting as proof of this proposition. Defendant also notes that his phone call to Rynders “clearly shows the Defendant put a halt to the attempted commission of the crime … but chose to do so by remaining friendly and cooperative with the hitman.”

Two distinct theories can be drawn from Defendant’s telephone conversation. The first, posited by Defendant, is that Defendant wished to extricate himself from an agreed upon murder, but leave the “hit man” with the perception that the deal remained in place. However, there is a second equally plausible theory which was presented by the State. That is, Defendant merely wanted to delay the previously planned murder, but leave the “hit man” with the knowledge that the deal remained in place.

Both theories were thoroughly argued to the jury. However, the jury chose to believe the State’s theory. Therefore, the jury could have properly concluded Defendant’s actions were “done toward the commission of the crime … the progress of which would be completed unless interrupted by some circumstances not intended in the original design” and not simply mere preparation.

… The Court today enters a lengthy analysis whether the acts constituted preparation or acts in the attempt to commit murder. … Minute examination between majority and minority views and “preparation” and “perpetration” conflict with the command of SDCL 22-1-1:

The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed has no application to this title. All its criminal and penal provisions and all penal statutes are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect their objects and promote justice.

Here there was evidence that all that was left was to pull the trigger. As the Court acknowledges “the law of attempts would be largely without function if it could not be invoked until the trigger was pulled.” … Thus, I respectfully dissent.

I join the Court’s legal analysis concerning the distinction between solicitations and attempts to commit murder [and I join the Court’s analysis of abandonment]. Therefore, I agree that Disanto’s solicitation of McCabe, in and of itself, was legally insufficient to constitute an attempt to commit murder… However, I respectfully disagree with the Court’s analysis of the facts, which leads it to find as a matter of law that Disanto “committed [no] act toward the commission of the offense[].” …[E]ven setting aside Disanto’s solicitation, he still engaged in sufficient other “acts” toward the commission of the murder such that reasonable jurors could have found that he proceeded “so far that they would result in the accomplishment of the crime unless frustrated by extraneous circumstances.” The intended victims were clearly in more danger then than they were when Disanto first expressed his desire to kill them.

Specifically, Disanto physically provided McCabe with a photograph of the victim, he pointed out her vehicle, and he took McCabe to the victim’s home and pointed her out as she was leaving. None of these acts were acts of solicitation. Rather, they were physical “act[s going] toward the commission” of the murder.

Although it is acknowledged that the cases discussed by the Court have found that one or more of the foregoing acts can be part of a solicitation, Disanto’s case has one significant distinguishing feature. After his solicitation was completed, after the details were arranged, and after Disanto completed the physical acts described above, he then went even further and executed a command to implement the killing. In fact, this Court itself describes this act as the “final command” to execute the murder. Disanto issued the order: “It’s a go.” This act is not present in the solicitation cases that invalidate attempted murder convictions because they proceeded no further than preparation.

Therefore, when Disanto’s final command to execute the plan is combined with his history and other acts, this is the type of case that proceeded further than the mere solicitations and plans found insufficient in the case law. This combination of physical acts would have resulted in accomplishment of the crime absent the intervention of the law enforcement officer. Clearly, the victim was in substantially greater danger after the final command than when Disanto first expressed his desire to kill her. Consequently, there was sufficient evidence to support an attempt conviction.[4]

It bears repeating that none of the various “tests” used by courts in this area of the law can possibly distinguish all preparations from attempts. Therefore, a defendant’s entire course of conduct should be evaluated in light of his intent and his prior history in order to determine whether there was substantial evidence from which a reasonable trier of fact could have sustained a finding of an attempt. In making that determination, it is universally recognized that the acts of solicitation and attempt are a continuum between planning and perpetration of the offense…

…[I]t is generally the jury’s function to determine whether those acts have proceeded beyond mere planning. As this Court itself has noted, where design is shown, “courts should not destroy the practical and common sense administration of the law with subtleties as to what constitutes [the] preparation” to commit a crime as distinguished from acts done towards the commission of a crime. …We leave this question to the jury because “[t]he line between preparation and attempt is drawn at that point where the accused’s acts no longer strike the jury as being equivocal but unequivocally demonstrate that a crime is about to be committed.”

I would follow that admonition and affirm the judgment of this jury. Disanto’s design, solicitation, physical acts toward commission of the crime and his final command to execute the murder, when considered together, unequivocally demonstrated that a crime was about to be committed. This was sufficient evidence from which the jury could have reasonably found that an attempt had been committed.

Notes and questions on State v. Disanto

- This case introduces two new concepts important to the study of inchoate offenses: solicitation, discussed in this note and the next few notes, and abandonment, discussed below. “Solicitation” is, roughly, the crime of trying to get someone else to commit a crime. When solicitation began to be treated as a crime by common law courts in the nineteenth century, it was typically defined as the act of asking, inducing, advising, ordering, or otherwise encouraging someone else to commit a crime. No separate mental state requirement was typically identified, and some modern solicitation statutes also omit an explicit reference to mental states. However, courts typically interpret solicitation to require intent that the other person (the solicitee) commit the target crime.

At the time Disanto was decided, South Dakota did not have a general solicitation statute. (That would soon change, as explained below.) Instead, separate statutes imposed criminal liability for certain types of offenses; it was a crime to solicit a bribe, for example, and a crime to solicit prostitution. But at the time that Mr. Disanto asked McCabe to kill Linda Olson, no statute made it criminal to solicit murder. Thus, the question before the state supreme court in this case was whether Disanto could be properly charged and convicted of attempted murder. Courts have divided on the question whether a solicitation—again, a request to someone else that they commit a crime—is itself sufficient to support attempt liability. What are the arguments for and against treating a solicitation as a form of attempt? There are a few different possible approaches that might be adopted by a jurisdiction: 1) all solicitations are attempts, making a separate crime of solicitation unnecessary; 2) some but not all solicitations are attempts; 3) solicitations are never attempts, but at least some solicitations should be separately criminalized; 4) solicitations are never attempts, and they should not be subject to criminal liability at all. Which position does the majority take? What about Justice Gilbertson? Justice Zinter?

- One year after this case was decided, South Dakota adopted the following general solicitation statute:

2005 South Dakota Laws Ch. 120, § 438, codified at SDCL § 22-4A-1. In 2021, the South Dakota Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Gilbertson (who dissented in Disanto), upheld a conviction under this statute for “solicitation to aid and abet a murder.” State v. Thoman, 955 N.W.2d 759 (2021). The defendant, William Thoman, had asked a friend “if he knew anyone that could do away with somebody,” and also asked the same friend to help him get a gun. Thoman expressed a desire to kill Dr. Mustafa Sahin, a doctor who had treated Thoman’s wife until her death from cancer. The friend, Kenneth Jones, later reported the conversation to law enforcement, who had Jones make a recorded phone call to Thoman.

Thoman, 955 N.W.2d at 764. Thoman was convicted of solicitation to murder under the new South Dakota statute. Should he have been convicted of attempted murder instead?

- The Disanto majority states, “[p]lainly, the evidence established that defendant repeatedly expressed an intention to kill Olson and Egemo, as well as Olson’s daughter, if necessary. As McCabe told the jury, defendant ‘was a man on a mission to have three individuals murdered.’” Contrast the majority’s characterization of the defendant’s mental state to the concurring opinion, which finds that “the evidence indicates that this blundering, broke, inept 59-year-old felon … was inadequate to pursue or execute this crime without the motivating encouragement of his ‘friend from prison’ and law enforcement officers. On his own, it would have been no more than a thought.” Are these two characterizations of McCabe’s intentions (and actions) consistent? If not, which seems more accurate to you?

- Disanto can help you refine your understanding of common law attempt terminology, including concepts discussed in Mandujano and the subsequent notes. The Disanto court distinguishes between “an unequivocal act [that] demonstrate[s] a crime is about to be committed unless frustrated by intervening circumstances” and “the last possible act before actual accomplishment of the crime.” Which of these two types of act is required to establish attempt liability in South Dakota?

- Notice that South Dakota has repealed by statute the common law principle of strict construction of criminal statutes. Both the majority opinion and Chief Justice Gilbertson’s dissent quote Section 22-1-1, but the majority opinion leaves out the first sentence of the statute. Check Justice Gilbertson’s dissent for the longer quotation. Does the extra sentence make a difference to the way you read the rest of the statute? In legal writing, lawyers often think carefully about what to quote and which sources to use. Professional norms generally require lawyers to avoid deliberate misrepresentation of a source. It is important to remember that judicial opinions are also advocacy documents in a certain sense: the judge who authors an opinion wants his or her readers to view the result as the only or best outcome, even if there were multiple possible interpretations of the underlying texts.

- Disanto argued that he “abandoned” any attempt to murder Olson. The majority suggests that “abandonment” is irrelevant if Disanto had already engaged in the “actus reus” of attempted murder—if he had taken sufficient action, along with his criminal intent, to become guilty of the crime of attempted murder. In some jurisdictions, however, a claim of “abandonment” can function as an affirmative defense to an attempted offense: even if the defendant has completed the necessary elements to be guilty of an attempted crime, his or her subsequent abandonment of the planned crime is relevant to criminal liability. For more on abandonment (sometimes called renunciation) as an affirmative defense, see People v. Acosta later in this chapter.

Check Your Understanding (8-3)

Impossibility

Michigan C.L.A. 750.92. Attempt to commit crime

Any person who shall attempt to commit an offense prohibited by law, and in such attempt shall do any act towards the commission of such offense, but shall fail in the perpetration, or shall be intercepted or prevented in the execution of the same, when no express provision is made by law for the punishment of such attempt, shall be punished as follows:

1. If the offense attempted to be committed is such as is punishable with death, the person convicted of such attempt shall be guilty of a felony, punishable by imprisonment in the state prison not more than 10 years;

2. If the offense so attempted to be committed is punishable by imprisonment in the state prison for life, or for 5 years or more, the person convicted of such attempt shall be guilty of a felony, punishable by imprisonment in the state prison not more than 5 years or in the county jail not more than 1 year;

3. If the offense so attempted to be committed is punishable by imprisonment in the state prison for a term less than 5 years, or imprisonment in the county jail or by fine, the offender convicted of such attempt shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, punishable by imprisonment in the state prison or reformatory not more than 2 years or in any county jail not more than 1 year or by a fine not to exceed 1,000 dollars; but in no case shall the imprisonment exceed ½ of the greatest punishment which might have been inflicted if the offense so attempted had been committed.

Michigan C.L.A. 750.157b. Solicitation to commit murder or other felony; affirmative defense

(1) For purposes of this section, “solicit” means to offer to give, promise to give, or give any money, services, or anything of value, or to forgive or promise to forgive a debt or obligation.

(2) A person who solicits another person to commit murder, or who solicits another person to do or omit to do an act which if completed would constitute murder, is guilty of a felony punishable by imprisonment for life or any term of years.

(3) Except as provided in subsection (2), a person who solicits another person to commit a felony, or who solicits another person to do or omit to do an act which if completed would constitute a felony, is punishable as follows:

(a) If the offense solicited is a felony punishable by imprisonment for life, or for 5 years or more, the person is guilty of a felony punishable by imprisonment for not more than 5 years or by a fine not to exceed $5,000.00, or both.

(b) If the offense solicited is a felony punishable by imprisonment for a term less than 5 years or by a fine, the person is guilty of a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for not more than 2 years or by a fine not to exceed $1,000.00, or both, except that a term of imprisonment shall not exceed ½ of the maximum imprisonment which can be imposed if the offense solicited is committed.

(4) It is an affirmative defense to a prosecution under this section that, under circumstances manifesting a voluntary and complete renunciation of his or her criminal purpose, the actor notified the person solicited of his or her renunciation and either gave timely warning and cooperation to appropriate law enforcement authorities or otherwise made a substantial effort to prevent the performance of the criminal conduct commanded or solicited, provided that conduct does not occur. The defendant shall establish by a preponderance of the evidence the affirmative defense under this subsection.

Michigan C.L.A. 722.675. Dissemination of sexually explicit material to minors

(1) A person is guilty of distributing obscene matter to a minor if that person does either of the following:

(a) Knowingly disseminates to a minor sexually explicit visual or verbal material that is harmful to minors.

* * *

(2) A person knowingly disseminates sexually explicit matter to a minor when the person knows both the nature of the matter and the status of the minor to whom the matter is disseminated.

(3) A person knows the nature of matter if the person either is aware of the character and content of the matter or recklessly disregards circumstances suggesting the character and content of the matter.

(4) A person knows the status of a minor if the person either is aware that the person to whom the dissemination is made is under 18 years of age or recklessly disregards a substantial risk that the person to whom the dissemination is made is under 18 years of age.

PEOPLE of the State of Michigan, Plaintiff–Appellant

v.

Christopher THOUSAND, Defendant–Appellee

Supreme Court of Michigan

631 N.W.2d 694

Decided July 27, 2001

YOUNG, J.

We granted leave in this case to consider whether the doctrine of “impossibility” provides a defense to a charge of attempt to commit an offense prohibited by law under M.C.L. § 750.92, or to a charge of solicitation to commit a felony under M.C.L. § 750.157b….

[Because this case has not yet been tried, our statement of facts is derived from preliminary hearings and documentation in the lower court record.] Deputy William Liczbinski was assigned by the Wayne County Sheriff’s Department to conduct an undercover investigation for the department’s Internet Crimes Bureau. Liczbinski was instructed to pose as a minor and log onto “chat rooms” on the Internet for the purpose of identifying persons using the Internet as a means for engaging in criminal activity.

On December 8, 1998, while using the screen name “Bekka,” Liczbinski was approached by defendant, who was using the screen name “Mr. Auto–Mag,” in an Internet chat room. Defendant described himself as a twenty-three-year-old male from Warren, and Bekka described herself as a fourteen-year-old female from Detroit. Bekka indicated that her name was Becky Fellins, and defendant revealed that his name was Chris Thousand. During this initial conversation, defendant sent Bekka, via the Internet, a photograph of his face.

From December 9 through 16, 1998, Liczbinski, still using the screen name “Bekka,” engaged in chat room conversation with defendant. During these exchanges, the conversation became sexually explicit. Defendant made repeated lewd invitations to Bekka to engage in various sexual acts, despite various indications of her young age.

During one of his online conversations with Bekka, after asking her whether anyone was “around there,” watching her, defendant indicated that he was sending her a picture of himself. Within seconds, Liczbinski received over the Internet a photograph of male genitalia. Defendant asked Bekka whether she liked and wanted it and whether she was getting “hot” yet, and described in a graphic manner the type of sexual acts he wished to perform with her. Defendant invited Bekka to come see him at his house for the purpose of engaging in sexual activity. Bekka replied that she wanted to do so, and defendant cautioned her that they had to be careful, because he could “go to jail.” Defendant asked whether Bekka looked “over sixteen,” so that if his roommates were home he could lie.

The two then planned to meet at an area McDonald’s restaurant at 5:00 p.m. on the following Thursday. Defendant indicated that they could go to his house, and that he would tell his brother that Bekka was seventeen. Defendant instructed Bekka to wear a “nice sexy skirt,” something that he could “get [his] head into.” Defendant indicated that he would be dressed in black pants and shirt and a brown suede coat, and that he would be driving a green Duster. Bekka asked defendant to bring her a present, and indicated that she liked white teddy bears.

On Thursday, December 17, 1998, Liczbinski and other deputy sheriffs were present at the … restaurant when they saw defendant inside a vehicle matching the description given to Bekka by defendant. Defendant … entered the restaurant. Liczbinski recognized defendant’s face from the photograph that had been sent to Bekka. Defendant looked around for approximately thirty seconds before leaving the restaurant. Defendant was then taken into custody [and his vehicle and home were searched].

Following a preliminary examination, defendant was bound over for trial on charges of solicitation to commit third-degree criminal sexual conduct, attempted distribution of obscene material to a minor, and child sexually abusive activity…

Defendant brought a motion to quash the information, arguing that, because the existence of a child victim was an element of each of the charged offenses, the evidence was legally insufficient to support the charges. The circuit court agreed and dismissed the case, holding that it was legally impossible for defendant to have committed the charged offenses. The Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal of the charges of solicitation and attempted distribution of obscene material to a minor….