3 Chapter Three: Enforcement Decisions

Sections in Chapter 3

Introduction

Police Decisions

Vagrancy Then and Now

Suspicion: A Closer Look

Prosecutorial Decisions

– Basic Requirements

– Discretion Not to Prosecute

– Discretion Among Offenses

Equal Protection and Other Possible Limitations

End of Chapter Review

Introduction

Suppose a criminalization decision has been made; a legislature has enacted a new criminal statute. Now what? The enactment of a statute does not, all by itself, generate any prosecutions or convictions. In this sense, a criminal statute is not self-enforcing. Legislatures do not monitor for violations, make arrests, or file charges. These enforcement tasks are instead allocated to executive branch officials—most importantly, police and prosecutors. This chapter offers an overview of police and prosecutorial authority, with a particular focus on the interaction between enforcement authority and criminal statutes.

A few key points are worth noting at the outset, and each should become more clear as you read the chapter. First, police and prosecutors typically have the authority to enforce any criminal statute in the jurisdiction. (We encountered this principle in Chapter One in our study of Commonwealth v. Copenhaver, where we were able to contrast the general enforcement authority of most police officers to the narrower enforcement powers of Pennsylvania county sheriffs.) Broad authority to enforce is the first key idea to keep in mind; the second is broad discretion. By discretion, we mean that enforcement officials typically have a choice about whether to enforce a given statute. For most offenses in most jurisdictions, enforcement is not mandatory. A police officer who observes or suspects an offense has the power to investigate and perhaps make an arrest, but the officer is not obligated to do so. And a prosecutor who receives a report or evidence of an offense has the power to bring charges, but is not obligated to do so.

In addition to authority and discretion, a third important theme of this chapter is suspicion, a topic not traditionally covered in first-year criminal law courses. You have probably often heard it said that a criminal conviction requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt. We will consider standards of proof, and the guilty pleas that are much more common than proof through presentation of evidence, in more detail in the next chapter. Here in this chapter, we focus on enforcement powers rather than convictions, and enforcement powers do not require proof. The power to search or to make an arrest arises as soon as a police officer has a legally adequate level of suspicion, and the same is true for a prosecutor’s power to file charges. This book does not seek to teach you suspicion doctrines in detail; you will look much more closely at the meaning of “reasonable suspicion” or “probable cause” if you take a course on investigative criminal procedure. But this chapter does introduce the basic concept of legally adequate suspicion, since it is the key threshold condition for many criminal law enforcement powers.

The combination of authority, discretion, and suspicion is a potent mix. Long before there is any proof of wrongdoing, and even in cases where no proof is ever established, police and prosecutors gain powers to intrude into individuals’ lives and curtail important liberties. The ability to act on suspicion rather than proof, and the fact of broad enforcement discretion, create opportunities for racial bias to shape criminal law outcomes. That is the final and most important theme to emphasize throughout this chapter: enforcement decisions as a source of significant racial disparities. Criminalization decisions and adjudication decisions can also contribute to racial inequality in criminal law, but enforcement may be the place where racial disparities are most easily identified and documented.

Police Decisions

In the early 1990s, many Chicago citizens were concerned about high levels of violence and drug crime. Many community members expressed particular concern about gang intimidation, reporting that members of criminal gangs would establish control over particular streets or areas and intimidate the residents of that area. In 1992, the city adopted the following ordinance, which was soon challenged in court.

Chicago Municipal Code, § 8–4–015

(a) Whenever a police officer observes a person whom he reasonably believes to be a criminal street gang member loitering in any public place with one or more other persons, he shall order all such persons to disperse and remove themselves from the area. Any person who does not promptly obey such an order is in violation of this section.

(b) It shall be an affirmative defense to an alleged violation of this section that no person who was observed loitering was in fact a member of a criminal street gang.

(c) As used in this Section:

(1) ‘Loiter’ means to remain in any one place with no apparent purpose.

(2) ‘Criminal street gang’ means any ongoing organization, association in fact or group of three or more persons, whether formal or informal, having as one of its substantial activities the commission of one or more of the criminal acts enumerated in paragraph (3), and whose members individually or collectively engage in or have engaged in a pattern of criminal gang activity.

…..

(5) ‘Public place’ means the public way and any other location open to the public, whether publicly or privately owned.

(e) Any person who violates this Section is subject to a fine of not less than $100 and not more than $500 for each offense, or imprisonment for not more than six months, or both.

In addition to or instead of the above penalties, any person who violates this section may be required to perform up to 120 hours of community service….

CITY OF CHICAGO, Petitioner

v.

Jesus MORALES et al.

Supreme Court of the United States

527 U.S. 41

Decided June 10, 1999

Justice STEVENS announced the judgment of the Court and delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to Parts I, II, and V, and an opinion with respect to Parts III, IV, and VI, in which Justice SOUTER and Justice GINSBURG join.

In 1992, the Chicago City Council enacted the Gang Congregation Ordinance, which prohibits “criminal street gang members” from “loitering” with one another or with other persons in any public place. The question presented is whether the Supreme Court of Illinois correctly held that the ordinance violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

I

… Commission of the offense involves four predicates. First, the police officer must reasonably believe that at least one of the two or more persons present in a “public place” is a “criminal street gang membe[r].” Second, the persons must be “loitering,” which the ordinance defines as “remain[ing] in any one place with no apparent purpose.” Third, the officer must then order “all” of the persons to disperse and remove themselves “from the area.” Fourth, a person must disobey the officer’s order. If any person, whether a gang member or not, disobeys the officer’s order, that person is guilty of violating the ordinance.

Two months after the ordinance was adopted, the Chicago Police Department promulgated … guidelines … to establish limitations on the enforcement discretion of police officers “to ensure that the anti-gang loitering ordinance is not enforced in an arbitrary or discriminatory way.” Chicago Police Department, General Order 92–4. [Only] sworn “members of the Gang Crime Section” and certain other designated officers [are authorized to make arrests under the ordinance, pursuant to] detailed criteria for defining street gangs and membership in such gangs. In addition, the order … provides that the ordinance “will be enforced only within … designated areas.” The city, however, does not release the locations of these “designated areas” to the public.

During the three years of its enforcement [before the ordinance was first held invalid in 1995], the police issued over 89,000 dispersal orders and arrested over 42,000 people for violating the ordinance. In the ensuing enforcement proceedings, 2 trial judges upheld the constitutionality of the ordinance, but 11 others ruled that it was invalid, with one court finding that the “ordinance fails to notify individuals what conduct is prohibited, and it encourages arbitrary and capricious enforcement by police.” … We granted certiorari, and now affirm. Like the Illinois Supreme Court, we conclude that the ordinance enacted by the city of Chicago is unconstitutionally vague.

III

The basic factual predicate for the city’s ordinance is not in dispute. As the city argues in its brief, “the very presence of a large collection of obviously brazen, insistent, and lawless gang members and hangers-on on the public ways intimidates residents, who become afraid even to leave their homes and go about their business. That, in turn, imperils community residents’ sense of safety and security, detracts from property values, and can ultimately destabilize entire neighborhoods.” The findings in the ordinance explain that it was motivated by these concerns. We have no doubt that a law that directly prohibited such intimidating conduct would be constitutional[1]but this ordinance broadly covers a significant amount of additional activity. Uncertainty about the scope of that additional coverage provides the basis for respondents’ claim that the ordinance is too vague.

… [An] imprecise laws[] may be impermissibly vague because it fails to establish standards for the police and public that are sufficient to guard against the arbitrary deprivation of liberty interests. .. [A]s the United States recognizes, the freedom to loiter for innocent purposes is part of the “liberty” protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. We have expressly identified this “right to remove from one place to another according to inclination” as “an attribute of personal liberty” protected by the Constitution. Williams v. Fears, 179 U.S. 270 (1900); see also Papachristou v. Jacksonville, 405 U.S. 156 (1972).[2]

… [I]t is clear that the vagueness of this enactment makes a facial challenge appropriate. This is not an ordinance that “simply regulates business behavior and contains a scienter requirement.” It is a criminal law that contains no mens rea requirement, and infringes on constitutionally protected rights.

Vagueness may invalidate a criminal law for either of two independent reasons. First, it may fail to provide the kind of notice that will enable ordinary people to understand what conduct it prohibits; second, it may authorize and even encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement….

IV

“It is established that a law fails to meet the requirements of the Due Process Clause if it is so vague and standardless that it leaves the public uncertain as to the conduct it prohibits….” Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966). [T]he definition of [“loiter”] in this ordinance—“to remain in any one place with no apparent purpose”—does not [have a clear meaning]. It is difficult to imagine how any citizen of the city of Chicago standing in a public place with a group of people would know if he or she had an “apparent purpose.” If she were talking to another person, would she have an apparent purpose? If she were frequently checking her watch and looking expectantly down the street, would she have an apparent purpose?

Since the city cannot conceivably have meant to criminalize each instance a citizen stands in public with a gang member, the vagueness that dooms this ordinance is not the product of uncertainty about the normal meaning of “loitering,” but rather about what loitering is covered by the ordinance and what is not. The Illinois Supreme Court emphasized the law’s failure to distinguish between innocent conduct and conduct threatening harm. [Although] a number of state courts that have upheld ordinances that criminalize loitering combined with some other overt act or evidence of criminal intent[,] state courts have uniformly invalidated laws that do not join the term “loitering” with a second specific element of the crime.

The city’s principal response to this concern about adequate notice is that loiterers are not subject to sanction until after they have failed to comply with an officer’s order to disperse. “[W]hatever problem is created by a law that criminalizes conduct people normally believe to be innocent is solved when persons receive actual notice from a police order of what they are expected to do.” We find this response unpersuasive for at least two reasons.

… If the loitering is in fact harmless and innocent, the dispersal order itself is an unjustified impairment of liberty. Because an officer may issue an order only after prohibited conduct has already occurred, [the officer’s order] cannot provide the kind of advance notice that will protect the putative loiterer from being ordered to disperse. Such an order cannot retroactively give adequate warning of the boundary between the permissible and the impermissible applications of the law.

Second, the terms of the dispersal order compound the inadequacy of the notice…. It provides that the officer “shall order all such persons to disperse and remove themselves from the area.” This vague phrasing raises a host of questions. After such an order issues, how long must the loiterers remain apart? How far must they move? If each loiterer walks around the block and they meet again at the same location, are they subject to arrest or merely to being ordered to disperse again? …

The Constitution does not permit a legislature to “set a net large enough to catch all possible offenders, and leave it to the courts to step inside and say who could be rightfully detained, and who should be set at large.” United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214 (1876). This ordinance is … vague “not in the sense that it requires a person to conform his conduct to an imprecise but comprehensible normative standard, but rather in the sense that no standard of conduct is specified at all.”

V

The broad sweep of the ordinance also violates “the requirement that a legislature establish minimal guidelines to govern law enforcement.” Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. 352 (1983). There are no such guidelines in the ordinance. In any public place in the city of Chicago, persons who stand or sit in the company of a gang member may be ordered to disperse unless their purpose is apparent. The mandatory language in the enactment directs the police to issue an order without first making any inquiry about their possible purposes. It matters not whether the reason that a gang member and his father, for example, might loiter near Wrigley Field is to rob an unsuspecting fan or just to get a glimpse of Sammy Sosa leaving the ballpark; in either event, if their purpose is not apparent to a nearby police officer, she may—indeed, she “shall”—order them to disperse.

Recognizing that the ordinance does reach a substantial amount of innocent conduct, we turn, then, to its language to determine if it “necessarily entrusts lawmaking to the moment-to-moment judgment of the policeman on his beat.” Kolender. As we discussed in the context of fair notice, the principal source of the vast discretion conferred on the police in this case is the definition of loitering as “to remain in any one place with no apparent purpose.” As the Illinois Supreme Court interprets that definition, it “provides absolute discretion to police officers to decide what activities constitute loitering.” We have no authority to construe the language of a state statute more narrowly than the construction given by that State’s highest court….

It is true, as the city argues, that the requirement that the officer reasonably believe that a group of loiterers contains a gang member does place a limit on the authority to order dispersal. That limitation would no doubt be sufficient if the ordinance only applied to loitering that had an apparently harmful purpose or effect, or possibly if it only applied to loitering by persons reasonably believed to be criminal gang members. But this ordinance, for reasons that are not explained in the findings of the city council, requires no harmful purpose and applies to nongang members as well as suspected gang members. It applies to everyone in the city who may remain in one place with one suspected gang member as long as their purpose is not apparent to an officer observing them. Friends, relatives, teachers, counselors, or even total strangers might unwittingly engage in forbidden loitering if they happen to engage in idle conversation with a gang member….

In our judgment, the Illinois Supreme Court correctly concluded that the ordinance does not provide sufficiently specific limits on the enforcement discretion of the police “to meet constitutional standards for definiteness and clarity.” We recognize the serious and difficult problems testified to by the citizens of Chicago that led to the enactment of this ordinance…. However, in this instance the city has enacted an ordinance that affords too much discretion to the police and too little notice to citizens who wish to use the public streets.

Accordingly, the judgment of the Supreme Court of Illinois is

Affirmed.

Justice O’CONNOR, with whom Justice BREYER joins, concurring in part and concurring in the judgment.

… As it has been construed by the Illinois court, Chicago’s gang loitering ordinance is unconstitutionally vague because it lacks sufficient minimal standards to guide law enforcement officers. In particular, it fails to provide police with any standard by which they can judge whether an individual has an “apparent purpose.” Indeed, because any person standing on the street has a general “purpose”—even if it is simply to stand—the ordinance permits police officers to choose which purposes are permissible….

It is important to courts and legislatures alike that we characterize more clearly the narrow scope of today’s holding. As the ordinance comes to this Court, it is unconstitutionally vague. Nevertheless, there remain open to Chicago reasonable alternatives to combat the very real threat posed by gang intimidation and violence. For example, the Court properly and expressly distinguishes the ordinance from laws that require loiterers to have a “harmful purpose,” from laws that target only gang members, and from laws that incorporate limits on the area and manner in which the laws may be enforced. … Indeed, as the plurality notes, the city of Chicago has several laws that do [have these additional requirements]. Chicago has even enacted a provision that “enables police officers to fulfill … their traditional functions,” including “preserving the public peace.” Specifically, Chicago’s general disorderly conduct provision allows the police to arrest those who knowingly “provoke, make or aid in making a breach of peace.” See Chicago Municipal Code § 8–4–010 (1992).

In my view, the gang loitering ordinance could have been construed more narrowly. The term “loiter” might possibly be construed in a more limited fashion to mean “to remain in any one place with no apparent purpose other than to establish control over identifiable areas, to intimidate others from entering those areas, or to conceal illegal activities.” Such a definition would be consistent with the Chicago City Council’s findings and would avoid the vagueness problems of the ordinance as construed by the Illinois Supreme Court….

The Illinois Supreme Court did not choose to give a limiting construction to Chicago’s ordinance. …[W]e cannot impose a limiting construction that a state supreme court has declined to adopt. Accordingly, I join Parts I, II, and V of the Court’s opinion and concur in the judgment.

[Partial concurrences by Justices KENNEDY and BREYER, each concurring in the judgment, omitted.]

Justice SCALIA, dissenting.

The citizens of Chicago were once free to drive about the city at whatever speed they wished. At some point Chicagoans (or perhaps Illinoisans) decided this would not do, and imposed prophylactic speed limits designed to assure safe operation by the average (or perhaps even subaverage) driver with the average (or perhaps even subaverage) vehicle. This infringed upon the “freedom” of all citizens, but was not unconstitutional.

… Until the ordinance that is before us today was adopted, the citizens of Chicago were free to stand about in public places with no apparent purpose—to engage, that is, in conduct that appeared to be loitering. In recent years, however, the city has been afflicted with criminal street gangs. As reflected in the record before us, these gangs congregated in public places to deal in drugs, and to terrorize the neighborhoods by demonstrating control over their “turf.” Many residents of the inner city felt that they were prisoners in their own homes. Once again, Chicagoans decided that to eliminate the problem it was worth restricting some of the freedom that they once enjoyed. The means they took was similar to the second, and more mild, example given above rather than the first: Loitering was not made unlawful, but when a group of people occupied a public place without an apparent purpose and in the company of a known gang member, police officers were authorized to order them to disperse, and the failure to obey such an order was made unlawful. The minor limitation upon the free state of nature that this prophylactic arrangement imposed upon all Chicagoans seemed to them (and it seems to me) a small price to pay for liberation of their streets.

I

… Both the plurality opinion and the concurrences display a lively imagination, creating hypothetical situations in which the law’s application would (in their view) be ambiguous. But that creative role has been usurped from petitioner, who can defeat respondents’ facial challenge by conjuring up a single valid application of the law. My contribution would go something like this [with apologies to the creators of West Side Story]: Tony, a member of the Jets criminal street gang, is standing alongside and chatting with fellow gang members while staking out their turf at Promontory Point on the South Side of Chicago; the group is flashing gang signs and displaying their distinctive tattoos to passersby. Officer Krupke, applying the ordinance at issue here, orders the group to disperse. After some speculative discussion (probably irrelevant here) over whether the Jets are depraved because they are deprived, Tony and the other gang members break off further conversation with the statement—not entirely coherent, but evidently intended to be rude—“Gee, Officer Krupke, krup you.” A tense standoff ensues until Officer Krupke arrests the group for failing to obey his dispersal order. Even assuming (as the Justices in the majority do, but I do not) that a law requiring obedience to a dispersal order is impermissibly vague unless it is clear to the objects of the order, before its issuance, that their conduct justifies it, I find it hard to believe that the Jets would not have known they had it coming. That should settle the matter of respondents’ facial challenge to the ordinance’s vagueness.

II

…[T]here is not the slightest evidence for the existence of a genuine constitutional right to loiter. Justice THOMAS recounts the vast historical tradition of criminalizing the activity….

III

[The plurality claims that] this criminal ordinance contains no mens rea requirement. The first step in analyzing this proposition is to determine what the actus reus, to which that mens rea is supposed to be attached, consists of. The majority believes that loitering forms part of (indeed, the essence of) the offense, and must be proved if conviction is to be obtained. That is not what the ordinance provides. The only part of the ordinance that refers to loitering is the portion that addresses, not the punishable conduct of the defendant, but what the police officer must observe before he can issue an order to disperse; and what he must observe is carefully defined in terms of what the defendant appears to be doing, not in terms of what the defendant is actually doing. The ordinance does not require that the defendant have been loitering (i.e., have been remaining in one place with no purpose), but rather that the police officer have observed him remaining in one place without any apparent purpose. Someone who in fact has a genuine purpose for remaining where he is (waiting for a friend, for example, or waiting to hold up a bank) can be ordered to move on (assuming the other conditions of the ordinance are met), so long as his remaining has no apparent purpose. It is likely, to be sure, that the ordinance will come down most heavily upon those who are actually loitering (those who really have no purpose in remaining where they are); but that activity is not a condition for issuance of the dispersal order.

The only act of a defendant that is made punishable by the ordinance—or, indeed, that is even mentioned by the ordinance—is his failure to “promptly obey” an order to disperse. The question, then, is whether that actus reus must be accompanied by any wrongful intent—and of course it must. As the Court itself describes the requirement, “a person must disobey the officer’s order.” No one thinks a defendant could be successfully prosecuted under the ordinance if he did not hear the order to disperse, or if he suffered a paralysis that rendered his compliance impossible. The willful failure to obey a police order is wrongful intent enough.

* * *

The fact is that the present ordinance is entirely clear in its application, cannot be violated except with full knowledge and intent, and vests no more discretion in the police than innumerable other measures authorizing police orders to preserve the public peace and safety. As suggested by their tortured analyses, and by their suggested solutions that bear no relation to the identified constitutional problem, the majority’s real quarrel with the Chicago ordinance is simply that it permits (or indeed requires) too much harmless conduct by innocent citizens to be proscribed. As Justice O’CONNOR’s concurrence says with disapprobation, “the ordinance applies to hundreds of thousands of persons who are not gang members, standing on any sidewalk … or other location open to the public.”

But in our democratic system, how much harmless conduct to proscribe is not a judgment to be made by the courts. So long as constitutionally guaranteed rights are not affected, and so long as the proscription has a rational basis, all sorts of perfectly harmless activity by millions of perfectly innocent people can be forbidden—riding a motorcycle without a safety helmet, for example, starting a campfire in a national forest, or selling a safe and effective drug not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration. All of these acts are entirely innocent and harmless in themselves, but because of the risk of harm that they entail, the freedom to engage in them has been abridged. The citizens of Chicago have decided that depriving themselves of the freedom to “hang out” with a gang member is necessary to eliminate pervasive gang crime and intimidation…. This Court has no business second-guessing either the degree of necessity or the fairness of the trade.

I dissent from the judgment of the Court.

Justice THOMAS, with whom THE CHIEF JUSTICE and Justice SCALIA join, dissenting.

…. By invalidating Chicago’s ordinance, I fear that the Court has unnecessarily sentenced law-abiding citizens to lives of terror and misery. The ordinance is not vague. “[A]ny fool would know that a particular category of conduct would be within [its] reach.” Kolender v. Lawson (1983) (White, J. dissenting)….

I

The human costs exacted by criminal street gangs are inestimable…. Gangs fill the daily lives of many of our poorest and most vulnerable citizens with a terror that the Court does not give sufficient consideration, often relegating them to the status of prisoners in their own homes…. The city of Chicago has suffered the devastation wrought by this national tragedy….

Before enacting its ordinance, the Chicago City Council held extensive hearings.… Following these hearings, the council found that “criminal street gangs establish control over identifiable areas … by loitering in those areas and intimidating others from entering those areas.” It further found that the mere presence of gang members “intimidate[s] many law abiding citizens” and “creates a justifiable fear for the safety of persons and property in the area.” It is the product of this democratic process—the council’s attempt to address these social ills—that we are asked to pass judgment upon today.

II

As part of its ongoing effort to curb the deleterious effects of criminal street gangs, the citizens of Chicago sensibly decided to return to basics. The ordinance does nothing more than confirm the well-established principle that the police have the duty and the power to maintain the public peace, and, when necessary, to disperse groups of individuals who threaten it….

The plurality’s sweeping conclusion that this ordinance infringes upon a liberty interest protected by the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause withers when exposed to the relevant history: Laws prohibiting loitering and vagrancy have been a fixture of Anglo–American law at least since the time of the Norman Conquest…. The American colonists enacted laws modeled upon the English vagrancy laws, and at the time of the founding, state and local governments customarily criminalized loitering and other forms of vagrancy. Vagrancy laws were common in the decades preceding the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, and remained on the books long after….

The Court concludes that the ordinance is also unconstitutionally vague because it fails to provide adequate standards to guide police discretion and because, in the plurality’s view, it does not give residents adequate notice of how to conform their conduct to the confines of the law. I disagree on both counts.

At the outset, it is important to note that the ordinance does not criminalize loitering per se. Rather, it penalizes loiterers’ failure to obey a police officer’s order to move along. A majority of the Court believes that this scheme vests too much discretion in police officers. Nothing could be further from the truth. Far from according officers too much discretion, the ordinance merely enables police officers to fulfill one of their traditional functions. Police officers are not, and have never been, simply enforcers of the criminal law. They wear other hats—importantly, they have long been vested with the responsibility for preserving the public peace….

In order to perform their peacekeeping responsibilities satisfactorily, the police inevitably must exercise discretion. Indeed, by empowering them to act as peace officers, the law assumes that the police will exercise that discretion responsibly and with sound judgment. That is not to say that the law should not provide objective guidelines for the police, but simply that it cannot rigidly constrain their every action. By directing a police officer not to issue a dispersal order unless he “observes a person whom he reasonably believes to be a criminal street gang member loitering in any public place,” Chicago’s ordinance strikes an appropriate balance between those two extremes. Just as we trust officers to rely on their experience and expertise in order to make spur-of-the-moment determinations about amorphous legal standards such as “probable cause” and “reasonable suspicion,” so we must trust them to determine whether a group of loiterers contains individuals (in this case members of criminal street gangs) whom the city has determined threaten the public peace. See Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690 (1996) (“Articulating precisely what ‘reasonable suspicion’ and ‘probable cause’ mean is not possible. They are commonsense, nontechnical conceptions that deal with the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act….”). In sum, the Court’s conclusion that the ordinance is impermissibly vague because it “necessarily entrusts lawmaking to the moment-to-moment judgment of the policeman on his beat” cannot be reconciled with common sense, longstanding police practice, or this Court’s Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.

… In concluding that the ordinance adequately channels police discretion, I do not suggest that a police officer enforcing the Gang Congregation Ordinance will never make a mistake. Nor do I overlook the possibility that a police officer, acting in bad faith, might enforce the ordinance in an arbitrary or discriminatory way. But … [i]nstances of arbitrary or discriminatory enforcement of the ordinance, like any other law, are best addressed when (and if) they arise, rather than prophylactically through the disfavored mechanism of a facial challenge on vagueness grounds.

Check Your Understanding (3-1)

Notes and questions about City of Chicago v. Morales

- When police stop an individual, question that person, or make an arrest, what is the source of their power? We first considered this question in Chapter One with Commonwealth v. Copenhaver. Recall that the majority of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court viewed the sheriff’s authority to stop or arrest as a matter of common law, while a partial dissenting opinion argued that the Pennsylvania legislature should define the scope of sheriffs’ authority by statute. In most jurisdictions, police are empowered – either by common law tradition or a statute – to enforce any criminal statute. (They are often empowered to enforce non-criminal statutes, such as civil traffic offenses, as well.) The Chicago ordinance under consideration in Morales seems to give the police a new power: the power to order persons to leave a given area when one or more of the persons gathered is suspected to belong to a criminal gang. If a person ordered to disperse does not do so, then the officer may make an arrest. Statutes that make it a crime to disobey a police officer’s order to disperse are fairly common, but to survive constitutional review, they usually must condition the officer’s power to order persons to disperse on specific circumstances such as an immediate threat to public safety. In Morales, the plurality concluded that given the ambiguity of the term “loitering,” the ordinance was too vague (even with its additional element of suspected gang membership) to meet constitutional requirements of due process.

- Why didn’t the police just arrest suspected gang members, instead of ordering them to disperse? “Being a gang member” is not itself a crime, and an attempt to criminalize gang membership itself could be subject to its own constitutional challenges, including the claim that it is a criminalization of status. (Recall the discussion of Robinson v. California and Powell v. Texas in the previous chapter.) But notice that the ordinance defined “criminal street gang” as a group that commits certain criminal acts, and notice also that a police superintendent reported that “90 percent” of the objectionable instances of “gang loitering” involved conduct that was separately criminalized. Why didn’t the police make arrests for “intimidation,” “gang conspiracy,” “disorderly conduct,” or other offenses, rather than rely upon the gang loitering statute? What benefits, to law enforcement officials or to the community more generally, are achieved by the gang loitering statute?

- The Chicago ordinance provided that “whenever” an officer observes gang loitering, he “shall” order the persons loitering to disperse. In a footnote not included above, the plurality observed that one could argue that the ordinance “affords the police no discretion, since it speaks with the mandatory ‘shall.’ However, not even the city makes this argument, which flies in the face of common sense that all police officers must use some discretion in deciding when and where to enforce city ordinances.” Morales, 527 U.S. at 63, n. 32. This is an important reminder that in almost all cases, the power of police to enforce statutes is discretionary – police have the option but not the obligation to enforce a given statute. There are specific exceptions to this rule. For example, some jurisdictions have enacted domestic violence statutes with mandatory arrest provisions in an attempt to counter patterns of nonenforcement. But mandatory arrest is a rare exception and not the general rule. And even a mandatory arrest provision may prove difficult to enforce if police simply decline to make the arrest. See Castle Rock v. Gonzales, 545 U.S. 748 (2005).

- Analysis of the elements of the Chicago ordinance is not the main focus of any of the opinions in Morales, but each opinion rests on a particular interpretation of the law. As a reminder, it’s useful to practice statutory interpretation with each statute you encounter. The plurality characterized the Chicago ordinance as “a criminal law that contains no mens rea requirement.” Justice Scalia disagreed. What are the elements of the offense, including actus reus and mens rea, according to Scalia? According to the plurality? (Hint: look at the first paragraph of Part I of the plurality opinion, and Part III of Justice Scalia’s opinion.) Compare the plurality’s analysis, and Justice Scalia’s, to the text of the ordinance. Which interpretation seems most accurate to you?

- How did Chicago’s anti-loitering efforts play out on the street? In other words, what were the situations and circumstances that led to actual arrests under this ordinance? The U.S. Supreme Court did not go into factual details of specific arrests in its Morales opinion. However, in the defendants’ brief to the state supreme court, there are some descriptions of encounters that led to the arrests of Jesus Morales and other individuals charged with violating the Chicago anti-loitering law. As you read these descriptions, think about suspicion. How do police officers form the suspicion that someone is a gang member?

[Officer’s version:] Officer Matthew Craig testified at a bench trial that he observed Gregorio Gutierrez standing at the corner of Broadway and Winona Streets with two other men “doing absolutely nothing.” Officer Craig and his partner immediately told them to break up and leave the area. Officer Craig and his partner drove off around the block. When they returned, they saw Gutierrez standing at the same corner and arrested him for gang loitering. According to Officer Craig, Gutierrez had told him on previous occasions that he belonged to the Latin Kings.

[Defendant’s version:] Gregorio Gutierrez testified that he had left his home with his brother and was walking towards a nearby El stop to go to their mother’s place of employment. Along the way, they stopped to purchase a sandwich and soda from a store. Officer Craig and his partner drove up to them at the corner and arrested them without ever telling them to leave. When Gutierrez asked why he was being arrested, “they told us they don’t like us.” Gutierrez never told Officer Craig that he was a member of the Latin Kings. Gutierrez was no longer a member of the Latin Kings and was not a member on June 3, 1993. No one else with him at the corner was a member of the Latin Kings.

[Officer’s version:] At a bench trial, Officer Ray Frano testified that he saw approximately six young male Hispanics standing at the street corner by 1100 West Belmont “(t)alking to citizens on the street.” The neighborhood was predominately Caucasian. Officer Frano approached the Hispanic teenagers on the corner with the stated reason: “(b)ecause we wanted to know if they lived in the neighborhood or from the neighborhood.” He told the group of Hispanic teenagers that he would arrest them if they did not leave. Officer Frano left the scene. When he returned later, he arrested Jesus Morales and another person at the corner for gang loitering. According to Officer Frano, he believed Morales was a gang member because Morales wore blue and black clothing.

[Defendant’s version:] Jesus Morales testified that he was pausing at the intersection while walking on crutches home from a nearby hospital. After Morales told Officer Frano that he had no outstanding warrants, Officer Frano arrested him for gang loitering. Morales himself was not a gang member although he knew that the other person present on the corner was a Gangster Disciple.

Brief of Defendants-Appellees to Illinois Supreme Court, City of Chicago v. Morales, 1996 WL 33437124 (internal citations omitted).

- Consider the accounts above in relation to the statistics reported at the beginning of Part II of the Court’s opinion. The Court states that during the first three years that the ordinance was in effect, “the police issued over 89,000 dispersal orders and arrested over 42,000 people for violating the ordinance.” Assuming these figures are roughly accurate, nearly half of the people who received a dispersal order were ultimately arrested for violating the ordinance. Did half the people who were ordered to disperse simply refuse to do so? Or did police make arrests even without first giving an order to disperse, as suggested by some of the defendants?

- While the ordinance was in effect, the Chicago police department issued an order to guide officers in enforcement. This order stated that gang “membership may not be established solely because an individual is wearing clothing available for sale to the general public.” Chicago Police Department, General Order 92-4, quoted in City of Chicago v. Morales, 687 N.E.2d 53, 64 n. 1 (1997). Consider again Officer Frano’s explanations of why he approached Jesus Morales and then ordered him to disperse, quoted above in the excerpt from the defendants’ brief to the state court. Frano mentioned Morales’s clothing, but also the area: he noticed a group of “young male Hispanics” in a predominantly Caucasian neighborhood and wanted to know if they were “from the neighborhood.” Is it fair to say that the ingredients of suspicion here are clothing, race, and place?

- In fact, most persons prosecuted under the Chicago ordinance were Black or Latino. See Dorothy Roberts, Foreword: Race, Vagueness, and the Social Meaning of Order Maintenance Policing, 89 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 775, 776 n. 2 (1999). At the same time, defenders of the ordinance, including the Morales dissenters, argued that minority communities supported the ordinance as a way to make their neighborhoods safer. Professor Roberts reports that Blacks and other minority residents actually held conflicting opinions about the ordinance. Should the possibility of racialized patterns of enforcement affect the criminalization decision – that is, the legislative decision to enact a new law? How, if at all, should racialized patterns of enforcement affect the constitutional review of a criminal statute? We return to this question with United States v. Armstrong later in this chapter.

- Across jurisdictions, the racialized conception of a “gang” has drawn scholarly attention. Some scholars argue that gangs do tend to be composed of members of the same minority racial group. Others have argued that systemic racial biases shape the labeling of groups as “gangs,” with law enforcement less likely to classify a group of white persons as a criminal gang. For citations to the literature and a close analysis of the “gang” designation in federal prosecutions, see Jordan Blair Woods, Systemic Racial Bias and RICO’s Application to Criminal Street and Prison Gangs, 17 Mich. J. Race & L. 303 (2012).

- Void-for-vagueness doctrine is often said to address two separate concerns: first, the worry that a vague law will fail to give individuals fair warning, or notice, that specific conduct will be subject to criminal liability; and second, the worry that a vague law will enable arbitrary or discriminatory enforcement. Notice the connection between discretion and the possibility of discrimination: if police have wide discretion to select persons for loitering arrests, there arises the possibility that they will select persons for arrest on the basis of race (or some other factor not identified in the statute). A third concern, related to the first two, is that vague statutes can blur or collapse the distinction between criminalization decisions and enforcement decisions, so that in effect police decide what conduct is criminal. To express this worry, the Morales plurality quoted Kolender v. Lawson (1983), an earlier decision striking down a loitering statute on vagueness grounds, in part because the statute “necessarily entrust[ed] lawmaking to the moment-to-moment judgment of the policeman on his beat.”

- In their dissents, Justice Scalia and Thomas pointed out that American criminal laws have long criminalized “loitering and other forms of vagrancy.” To Scalia and Thomas, this historical tradition was relevant because it suggested that Chicago acted well within its constitutional powers in criminalizing gang loitering. The Morales plurality responded by alluding to the racialized history of vagrancy law, especially the use of vagrancy prosecutions after the Civil War to push Black Americans into forced labor. See footnote 2 above, which was footnote 20 of the unedited opinion. The history of vagrancy offers an important illustration of the interaction between broad criminalization and broad enforcement discretion, as explored later in this chapter.

- In 2000, Chicago adopted a revised gang loitering ordinance, taking guidance from Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinion in Morales, and perhaps also from vagrancy statutes that survived constitutional challenges. The new ordinance defines gang loitering as “remaining in any one place under circumstances that would warrant a reasonable person to believe that the purpose or effect of that behavior is to enable a criminal street gang to establish control over identifiable areas, to intimidate others from entering those areas, or to conceal illegal activities.” Chi. Ill. Mun. Code § 8-5-015 (2000). Do you think the new law avoids the problems of notice or enforcement discretion that the Court found in the first version of the law?

Vagrancy Then and Now

“Laws prohibiting loitering and vagrancy have been a fixture of Anglo-American law at least since the time of the Norman Conquest,” wrote Justice Thomas in his dissent in City of Chicago v. Morales. Morales explored the meaning of the term loiter, but what is “vagrancy”? The term is often associated with idleness, but as a criminal offence, vagrancy is notoriously hard to define. Arguably, that is the point of the term: to capture an array of behaviors or conditions that are not easily defined in a written statute. Here is one typical vagrancy statute:

Rogues and vagabonds, or dissolute persons who go about begging, common gamblers, persons who use juggling or unlawful games or plays, common drunkards, common night walkers, thieves, pilferers or pickpockets, traders in stolen property, lewd, wanton and lascivious persons, keepers of gambling places, common railers and brawlers, persons wandering or strolling around from place to place without any lawful purpose or object, habitual loafers, disorderly persons, persons neglecting all lawful business and habitually spending their time by frequenting houses of ill fame, gaming houses, or places where alcoholic beverages are sold or served, persons able to work but habitually living upon the earnings of their wives or minor children shall be deemed vagrants and, upon conviction in the Municipal Court shall be punished as provided for Class D offenses.

What is a rogue, a vagabond, a wanton person, a habitual loafer? This particular statute, Jacksonville Ordinance Code § 26-57, was found to be unconstitutionally vague in Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville (1972). Until Papachristou, the legitimacy of vagrancy law was largely taken for granted, and even after Papachristou, new versions of vagrancy have persisted, as discussed below. According to one scholar, vagrancy laws were popular among ruling authorities for two reasons. “First, the laws’ breadth and ambiguity gave the police virtually unlimited discretion…. [I]t was almost always possible to justify a vagrancy arrest.” Risa Goluboff, Vagrant Nation 2 (2016). Additionally, “vagrancy laws made it a crime to be a certain type of person…. Where most American laws required people to do something criminal before they could be arrested, vagrancy laws emphatically did not.” Id. “The goals was to prevent crimes which may likely flow from a vagrant’s mode of life…. Such preventive purpose wholly fails if a law enforcement officer must wait until a crime is committed.” Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). Another function of vagrancy and loitering laws, echoed by Chicago’s approach to “gang loitering,” was simply to enable police to clear public spaces of people thought to be dangerous or otherwise undesirable. Once brought to court, many persons arrested for vagrancy would be offered dismissal of the charges on the condition that they leave the area and not return.

But in other contexts, the point of a vagrancy arrest was very different. As the Morales plurality mentioned [Fn. 2 in the opinion as edited above], “vagrancy laws were used after the Civil War to keep former slaves in a state of quasi slavery.” The Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolishes slavery “except as a punishment for crime.” After the Thirteenth Amendment was adopted, many southern states sought to replace the lost labor of enslaved persons through a practice known as “convict leasing.” Black men and women were arrested and prosecuted for vagrancy, then “leased” or “sold” to companies that would force them to labor. A Pulitzer-Prize-winning historical study of convict leasing opens with this example:

On March 30, 1908, Green Cottenham was arrested by the sheriff of Shelby County, Alabama, and charged with vagrancy.

Cottenham had committed no true crime. Vagrancy, the offense of a person not being able to prove at a given moment that he or she is employed, was … dredged up from legal obscurity at the end of the nineteenth century by the state legislatures of Alabama and other southern states. It was capriciously enforced by local sheriffs and constables, adjudicated by mayors and notaries public … and, most tellingly in a time of massive unemployment among all southern men, was reserved almost exclusively for black men. Cottenham’s offense was blackness.

… Cottenham was found guilty in a swift appearance before the county judge and immediately sentenced to a thirty-day term of hard labor. Unable to pay the array of fees assessed on every prisoner … Cottenham’s sentence was extended to nearly a year of hard labor. The next day, Cottenham was sold [to a mining company which would] pay off Cottenham’s fine and fees.

Douglas Blackmon, Slavery By Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (2008).

Convict leasing eventually came to an end after World War II, in part because of a change in enforcement decisions: federal prosecutors finally began to enforce the federal statutes that made “peonage,” or the use of forced labor, into a crime. Even so, the separate vagrancy statutes remained valid law. Indeed, even after the 1972 Papachristou decision struck down the Jacksonville vagrancy ordinance quoted above, and called into question the constitutionality of similar laws, vagrancy did not exactly fade to obscurity. Florida enacted a new vagrancy law that made it a crime “to loiter or prowl in a place, at a time or in a manner not usual for law-abiding individuals, under circumstances that warrant a justifiable and reasonable alarm or immediate concern for the safety of persons or property in the vicinity.” (See Goluboff, Vagrant Nation, p. 331.) Chicago similarly re-enacted a new version of its gang loitering ordinance after Morales, as discussed above. The revised Florida loitering law and the revised gang loitering ordinance are still in place as of 2021.

Suspicion: A Closer Look

City of Chicago v. Morales concerned a statute that specifically empowered police to act in particular way—to order persons to disperse. Most criminal statutes don’t explicitly authorize police actions or even mention the police at all, but any criminal statute is nonetheless a source of power for the police. That is because police are generally empowered to stop and arrest persons, or conduct other investigative activities, whenever they have adequate suspicion of criminal activity. In other words, if a statute defines a crime of “knowing conversion” of government property, like the statute that was applied in United States v. Morissette in Chapter Two, then an officer who has legally adequate suspicion of knowing conversion is automatically empowered to stop, question, or arrest the person suspected of this offense. You first encountered this point with Commonwealth v. Copenhaver in Chapter One, but it is sufficiently important to emphasize again: once an act is defined as criminal, state officials have not only the authority to punish that act, but also the authority to police it – to investigate, search, and arrest when the officials suspect that someone has engaged or is going to engage in the proscribed act.

The requisite levels of suspicion are defined primarily by constitutional doctrine. The Fourth Amendment prohibits “unreasonable searches and seizures,” and this language is the basis of the constitutional framework to evaluate police stops, searches, arrests, and other investigative activities. In the course of interpreting the Fourth Amendment, the Supreme Court has determined that a reasonable search or seizure is one that is based on “reasonable suspicion” of criminal activity or “probable cause” to believe that a crime has occurred.

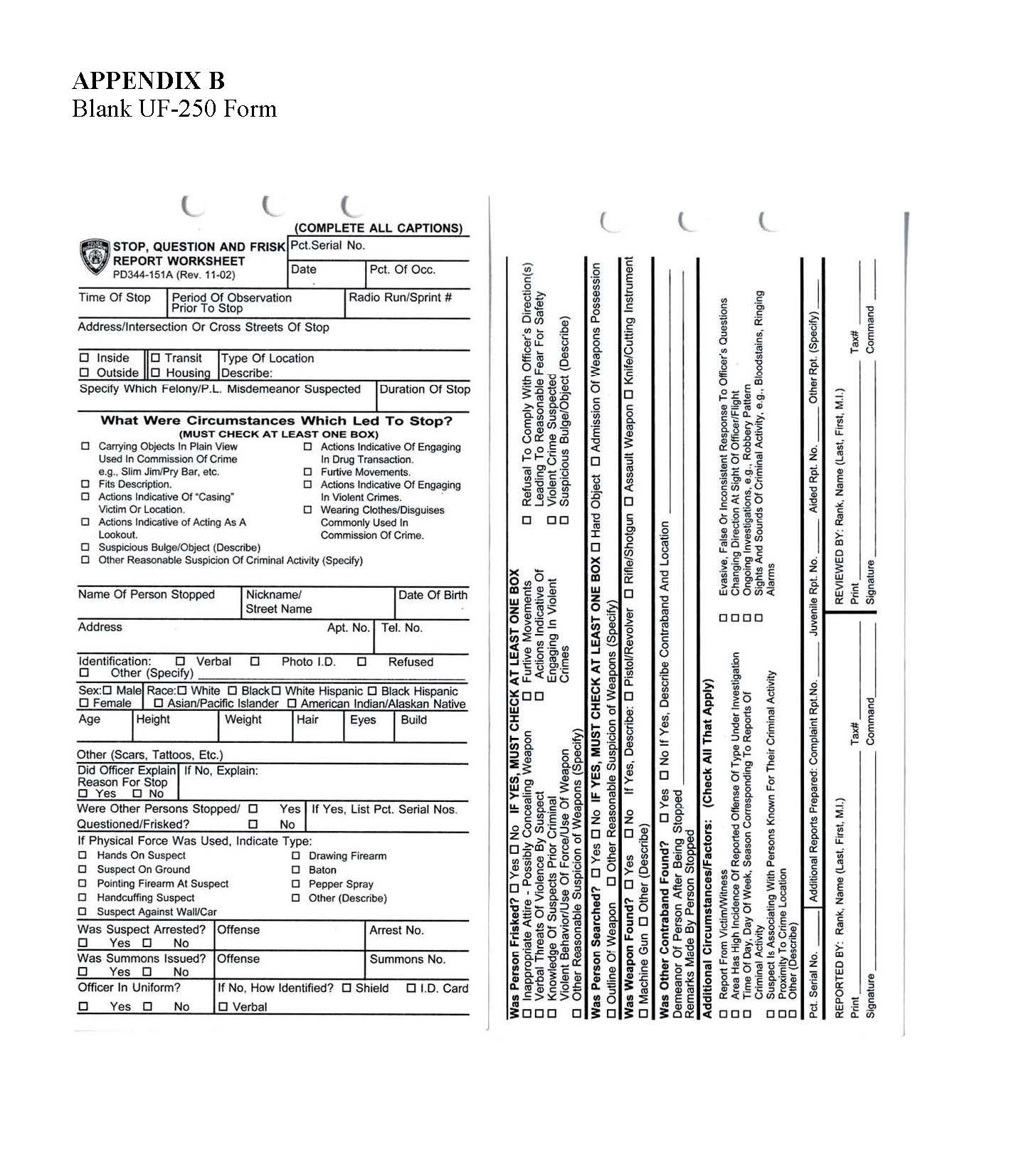

“Reasonable suspicion” and “probable cause” are notoriously ambiguous concepts, but each of these legal standards generally requires an officer to identify some attribute of the individual person or place that led the officer to suspect criminal activity. An officer can establish reasonable suspicion by noting that the individual matched a description of a specific suspect, for example, or was behaving in a manner known to the officer to be characteristic of persons engaged in narcotics trafficking. Officers are empowered to stop and question an individual whenever they have “reasonable suspicion,” but a full arrest requires “probable cause.” The Supreme Court has said very little about the distinction between reasonable suspicion and probable cause, other than to indicate that probable cause is a slightly higher threshold than reasonable suspicion. But either standard is relatively easy for officers to satisfy. A record-keeping form used by the New York Police Department, UF-250, is reproduced below to give you an idea of the kinds of observations police frequently invoke to establish reasonable suspicion. For example, the UF-250 form identifies as possible reasons for a stop, “furtive movements,” “wearing clothing/disguises commonly used in commission of crime,” “area has high incidence of reported offense of type under investigation,” and “changing direction at sight of officer / flight.”

Given that reasonable suspicion and probable cause are low thresholds, police officers will have the legal authority to stop, question, or arrest many more individuals than they can actually pursue. That means that officers must choose when, given the presence of reasonable suspicion or probable cause, they will actually initiate an investigation. What factors influence this choice? How do officers decide which persons merit a stop or arrest, and which ones can be ignored? Police officers are not necessarily motivated by the same goals as prosecutors. Prosecutors are typically more focused on securing convictions than police officers are. Officers may have more immediate aims, such as to resolve a present conflict, to preserve order, or to protect their own authority. They may make an arrest without necessarily expecting a conviction to be the ultimate result.

The UF-250 form presented above provides one source of insight into police decisionmaking. Over the course of litigation against the New York Police Department, advocates and social scientists analyzed extensive data concerning millions of police stops, including details of the factors cited by police as giving rise to suspicion. The analysis suggested that, especially when pressured by commanders to maximize the number of people stopped, officers followed certain “scripts” to rationalize stops based on very little information about the individual who is stopped. Over time, officers identified “evasive / furtive movements” and “high crime area” with increasing frequency as reasons for stops. See Jeffrey Fagan & Amanda Geller, Following the Script: Narratives of Suspicion in Terry Stops in Street Policing, 82 U. Chi. L. Rev. 51 (2015).

The UF-250 form tracks other information beyond the basis of suspicion, such as the race of the person stopped, whether the police used force, whether the police did find a weapon or other contraband. By analyzing records of millions of stops, litigants were able to establish that police stopped Black and Latino persons, and used force against them, disproportionately often in relation to the overall population of these groups in New York City. But the police were actually slightly more likely to find weapons or other contraband when they stopped white persons (perhaps because stops of white persons were based on more careful determinations of suspicion). See Floyd v. City of New York, 959 F. Supp. 2d 540, 558-559 (S.D.N.Y. 2013). The Floyd court found that “blacks are likely targeted for stops based on a lesser degree of objectively founded suspicion than whites,” id. at 560, and the court found NYPD’s stop-and-frisk practices to violate both the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments.

The data discussed by the Floyd court is consistent with broader empirical data discussed in Chapter One: persons of color (especially Black persons) are subject to criminal interventions, including stops and arrests, disproportionately often. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Fourth Amendment does not prohibit police from using race as a relevant factor in selecting among persons to stop or arrest (so long as the police can satisfy the reasonable suspicion or probable cause standards), but other provisions of the federal constitution may prohibit race-based enforcement choices. The last section of this chapter considers equal protection doctrine and its application to both policing and prosecutorial choices.

You will have the opportunity to study Fourth Amendment law in much more detail in an upper-level course on constitutional criminal procedure. For purposes of this first-year course, you need not worry about the nuances of either of the Fourth Amendment suspicion thresholds mentioned above, “probable cause” or “reasonable suspicion.” It is enough to know that once an officer does have the requisite suspicion that a person is engaging in, or has engaged in, a crime, the officer is then empowered to investigate further. And because the Fourth Amendment suspicion thresholds are low, officers usually have the opportunity, and indeed the necessity, to select some individuals for further investigation and let others go.

There is thus some tension between Fourth Amendment doctrine, which grants police broad discretion, and the void-for-vagueness doctrine as presented by the plurality in Chicago v. Morales. Justice Thomas noted this tension in his Morales dissent, arguing that we should simply embrace police discretion in both contexts: “Just as we trust officers to rely on their experience and expertise to make spur-of-the-moment determinations about amorphous legal standards such as ‘probable cause’ and ‘reasonable suspicion,’ so we must trust them to determine whether a group of loiterers contains individuals (in this case members of criminal street gangs) whom the city has determined threaten the public peace.” City of Chicago v. Morales, 527 U.S. 41, 109-110 (1999) (Thomas, J., dissenting). One scholar has argued that “vagueness doctrine is best seen as an adjunct to Fourth Amendment law, not as a serious check on crime definition.” William J. Stuntz, The Political Constitution of Criminal Justice, 119 Harv. L. Rev. 780, 790 n. 54 (2006).

Prosecutorial Decisions

Basic Requirements

It is a prosecutor, not a police officer, who decides whether a person suspected of criminal activity, or even arrested for it, will ultimately be formally charged with a crime. Charging decisions include choices such as whether a given person will be charged at all; which offense or offenses will be charged; whether charges will later be dropped or added. Prosecutors typically have the power to make these decisions with relatively few constraints. A victim or a police officer may file a complaint alleging the commission of a crime, but even then, it is usually the prosecutor who decides whether to file formal charges. In most U.S. jurisdictions, the minimum threshold for a formal charge is again “probable cause” – a prosecutor should not bring charges if the evidence does not establish “probable cause” to believe the defendant is guilty. As in the context of police decisions, probable cause is a difficult-to-define term that does not express a specific probability that the defendant is guilty. A typical explanation of probable cause is that it requires “a reasonable ground for belief in guilt.” Later in this book, we will consider some cases in which courts evaluate whether sufficient evidence exists to establish probable cause for a specific charge. But to emphasize: once the probable cause threshold is crossed, whether to bring charges at all, and which charges to bring, is a matter of prosecutorial discretion.

The prosecutor’s charging decision is usually recorded in a charging document, which could be called an information, a complaint, or an indictment. Depending on the jurisdiction, the prosecutor may be able to initiate charges at his or her sole discretion, or he or she may need to obtain an indictment from a grand jury—a group of jurors who hear the prosecution’s statement of evidence (but usually not any evidence from the defense) and who then determine whether there is sufficient probable cause to proceed with the charges. We saw the text of an indictment in Commonwealth v. Mochan, the very first case we read in Chapter One. In Mochan, the defendant was prosecuted under Pennsylvania common law rather than a specific statute. Today, since common law crimes have been abolished in most jurisdictions, an indictment will generally refer to a specific statute or statutes. For one example, you can find the text of the indictment in United States v. Morissette in Chapter Two. An indictment should allege all the specific elements of the charged offense; otherwise, a court may find it “deficient” and dismiss the charges. But an indictment is not itself evidence; it states the allegations against the defendant but does not prove them.

Charging decisions are often revisited or revised over the course of a criminal case. For example, a prosecutor may file an indictment, then later file a superseding indictment that adds new charges. And plea negotiations with the defense will often involve agreements to drop or reduce charges in exchange for a guilty plea. Overlapping statutes, previously mentioned in Chapter Two, are especially useful to prosecutors in this context. If there are multiple statutes that could plausibly be applied to a defendant’s conduct, the prosecutor may be able to threaten multiple convictions and a more severe penalty, then offer reduced charges and a less severe sentence in exchange for a guilty plea. We will consider this aspect of prosecutorial discretion in more detail later in this chapter.

Check Your Understanding (3-2)

Discretion Not to Prosecute

The previous section identified the basic requirements a prosecutor must fulfill in order to bring a charge. But what if a prosecutor decides not to bring any criminal charges? Do prosecutors have a duty to bring charges if they know of facts that indicate the violation of a criminal law?

INMATES OF ATTICA CORRECTIONAL FACILITY et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

Nelson A. ROCKEFELLER et al., Defendants-Appellees

U.S. Court of Appeals, Second Circuit

477 F.2d 375

Decided April 18, 1973

MANSFIELD, Circuit Judge:

…Plaintiffs … [include] certain present and former inmates of New York State’s Attica Correctional Facility (“Attica”) [and] the mother of an inmate who was killed…. The complaint alleges that before, during, and after the prisoner revolt at and subsequent recapture of Attica in September 1971, which resulted in the killing of 32 inmates and the wounding of many others, the defendants, including the Governor of New York [and various other state] officials, either committed, conspired to commit, or aided and abetted in the commission of various crimes against the complaining inmates and members of the class they seek to represent. It is charged that the inmates were intentionally subjected to cruel and inhuman treatment prior to the inmate riot, that State Police, Troopers, and Correction Officers … intentionally killed some of the inmate victims without provocation during the recovery of Attica, that state officers (several of whom are named and whom the inmates claim they can identify) assaulted and beat prisoners after the prison had been successfully retaken and the prisoners had surrendered, that personal property of the inmates was thereafter stolen or destroyed, and that medical assistance was maliciously denied to over 400 inmates wounded during the recovery of the prison.

The complaint further alleges that Robert E. Fischer, a Deputy State Attorney General specially appointed by the Governor … to investigate crimes relating to the inmates’ takeover of Attica and the resumption of control by the state authorities, “has not investigated, nor does he intend to investigate, any crimes committed by state officers.” Plaintiffs claim, moreover, that because Fischer was appointed by the Governor he cannot neutrally investigate the responsibility of the Governor and other state officers said to have conspired to commit the crimes alleged. It is also asserted that since Fischer is the sole state official currently authorized under state law to prosecute the offenses allegedly committed by the state officers, no one in the State of New York is investigating or prosecuting them.

With respect to the sole federal defendant, the United States Attorney for the Western District of New York, the complaint simply alleges that he has not arrested, investigated, or instituted prosecutions against any of the state officers accused of criminal violation of plaintiffs’ federal civil rights….

As a remedy for the asserted failure of the defendants to prosecute violations of state and federal criminal laws, plaintiffs request relief in the nature of mandamus (1) against state officials, requiring the State of New York to submit a plan for the independent and impartial investigation and prosecution of the offenses charged against the named and unknown state officers, and insuring the appointment of an impartial state prosecutor and state judge to “prosecute the defendants forthwith,” and (2) against the United States Attorney, requiring him to investigate, arrest and prosecute the same state officers for having committed [federal civil rights] offenses….

(1) Claim Against the United States Attorney

With respect to the defendant United States Attorney, plaintiffs seek mandamus to compel him to investigate and institute prosecutions against state officers, most of whom are not identified, for alleged violations of [federal law]. Federal mandamus is, of course, available only “to compel an officer or employee of the United States . . . to perform a duty owed to the plaintiff.” …[O]rdinarily the courts are “not to direct or influence the exercise of discretion of the officer or agency in the making of the decision.” More particularly, federal courts have traditionally and, to our knowledge, uniformly refrained from overturning, at the instance of a private person, discretionary decisions of federal prosecuting authorities not to prosecute persons regarding whom a complaint of criminal conduct is made.

This judicial reluctance to direct federal prosecutions at the instance of a private party asserting the failure of United States officials to prosecute alleged criminal violations has been applied even in cases such as the present one where, according to the allegations of the complaint, which we must accept as true for purposes of this appeal, serious questions are raised as to the protection of the civil rights and physical security of a definable class of victims of crime and as to the fair administration of the criminal justice system.

The primary ground upon which this traditional judicial aversion to compelling prosecutions has been based is the separation of powers doctrine. “Although as a member of the bar, the attorney for the United States is an officer of the court, he is nevertheless an executive official of the Government, and it is as an officer of the executive department that he exercises a discretion as to whether or not there shall be a prosecution in a particular case. It follows, as an incident of the constitutional separation of powers, that the courts are not to interfere with the free exercise of the discretionary powers of the attorneys of the United States in their control over criminal prosecutions.”

Although … this broad view [has been criticized as] unsound and incompatible with the normal function of the judiciary in reviewing for abuse or arbitrariness administrative acts that fall within the discretion of executive officers, … the manifold imponderables which enter into the prosecutor’s decision to prosecute or not to prosecute make the choice not readily amenable to judicial supervision.

In the absence of statutorily defined standards governing reviewability, or regulatory or statutory policies of prosecution, the problems inherent in the task of supervising prosecutorial decisions do not lend themselves to resolution by the judiciary. The reviewing courts would be placed in the undesirable and injudicious posture of becoming “superprosecutors.” In the normal case of review of executive acts of discretion, the administrative record is open, public and reviewable on the basis of what it contains. The decision not to prosecute, on the other hand, may be based upon the insufficiency of the available evidence, in which event the secrecy of the grand jury and of the prosecutor’s file may serve to protect the accused’s reputation from public damage based upon insufficient, improper, or even malicious charges. In camera review would not be meaningful without access by the complaining party to the evidence before the grand jury or U.S. Attorney. Such interference with the normal operations of criminal investigations, in turn, based solely upon allegations of criminal conduct, raises serious questions of potential abuse by persons seeking to have other persons prosecuted. Any person, merely by filing a complaint containing allegations in general terms (permitted by the Federal Rules) of unlawful failure to prosecute, could gain access to the prosecutor’s file and the grand jury’s minutes, notwithstanding the secrecy normally attaching to the latter by law.

Nor is it clear what the judiciary’s role of supervision should be…. At what point would the prosecutor be entitled to call a halt to further investigation as unlikely to be productive? What evidentiary standard would be used to decide whether prosecution should be compelled? How much judgment would the United States Attorney be allowed? Would he be permitted to limit himself to a strong “test” case rather than pursue weaker cases? … What sort of review should be available in cases like the present one where the conduct complained of allegedly violates state as well as federal laws? With limited personnel and facilities at his disposal, what priority would the prosecutor be required to give to cases in which investigation or prosecution was directed by the court?

These difficult questions engender serious doubts as to the judiciary’s capacity to review and as to the problem of arbitrariness inherent in any judicial decision to order prosecution. On balance, we believe that substitution of a court’s decision to compel prosecution for the U.S. Attorney’s decision not to prosecute, even upon an abuse of discretion standard of review and even if limited to directing that a prosecution be undertaken in good faith, … would be unwise.

Plaintiffs urge, however, that Congress withdrew the normal prosecutorial discretion for the kind of conduct alleged here by providing … that the United States Attorneys are “authorized and required . . . to institute prosecutions against all persons violating any of the provisions of 18 U.S.C. §§ 241, 242” (emphasis supplied), and, therefore, that no barrier to a judicial directive to institute prosecutions remains. This contention must be rejected. The mandatory nature of the word “required” … is insufficient to evince a broad Congressional purpose to bar the exercise of executive discretion in the prosecution of federal civil rights crimes. Similar mandatory language is contained in [various other federal statutes].

Such language has never been thought to preclude the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. Indeed the same contention made here was specifically rejected in Moses v. Kennedy, 219 F. Supp. 762 (D.D.C. 1963), where seven black residents and one white resident of Mississippi sought mandamus to compel the Attorney General of the United States and the Director of the F.B.I. to investigate, arrest, and prosecute certain individuals, including state and local law enforcement officers, for willfully depriving the plaintiffs of their civil rights. There the Court noted that “considerations of judgment and discretion apply with special strength to the area of civil rights, where the Executive Department must be largely free to exercise its considered judgment on questions of whether to proceed by means of prosecution, injunction, varying forms of persuasion, or other types of action.”

… It therefore becomes unnecessary to decide whether, if Congress were by explicit direction and guidelines to remove all prosecutorial discretion with respect to certain crimes or in certain circumstances we would properly direct that a prosecution be undertaken.

(2) Claims Against the State Officials

With respect to the state defendants, plaintiffs also seek prosecution of named and unknown persons for the violation of state crimes. However, they have pointed to no statutory language even arguably creating any mandatory duty upon the state officials to bring such prosecutions. To the contrary, New York law reposes in its prosecutors a discretion to decide whether or not to prosecute in a given case, which is not subject to review in the state courts….

Plaintiffs point to language in our earlier opinion, Inmates of Attica Correctional Facility v. Rockefeller, 453 F.2d 12, 20 (2d Cir. 1971), to the effect that “the State has the duty to investigate and prosecute all persons, including inmates, who may have engaged in criminal conduct before, during and after the uprising.” But the statement does not support their present demands. The existence of such a duty does not define its dimensions or imply that an alleged failure to perform the duty completely or equally, as between inmates and state officials, will support federal judicial supervision of state criminal prosecutions. The serious charge that the state’s investigation is proceeding against inmates but not against state officers, if shown to be accurate, might lead the Governor to supplement or replace those presently in charge of the investigation or the state legislature to act. But the gravity of the allegation does not reduce the inherent judicial incapacity to supervise.

The only authority supporting the extraordinary relief requested here is the Seventh Circuit’s recent decision in Littleton v. Berbling, 468 F.2d 389 (1972), cert. granted, 411 U.S. 915 (1973). There a class of black citizens of Cairo, Illinois, brought suit for damages and injunctive relief against a state prosecutor, an investigator for him, a magistrate and a state judge, charging that the defendants had “systematically applied the state criminal laws so as to discriminate against plaintiffs and their class on the basis of race, interfering thereby with the free exercise of their constitutional rights.” They alleged a long history indicating a concerted pattern of officially sponsored racial discrimination. In reversing the district court’s dismissal of the complaint, a divided panel concluded that a state judge … may be enjoined from unconstitutionally fixing bails and imposing sentences that discriminated sharply against black persons, and that the State Attorney’s quasi-judicial immunity from suit for damages when performing his prosecutorial function “does not extend to complete freedom from injunction.” Finding other possible remedies either unavailable or ineffective, the Court approved the possibility of some type of injunctive relief, not fully specified, but which might include a requirement of “periodic reports of various types of aggregate data on actions on bail and sentencing and dispositions of complaints.”

However, the decision in Littleton is clearly distinguishable. There the claim, unlike that here, alleged a systematic and lengthy course of egregious racial discrimination in which black persons were denied equal access to and treatment by the state criminal justice system. Furthermore, the Court’s decision does not appear to have compelled the institution of criminal prosecutions, which is the principal relief sought here. In short, we believe that Littleton should be strictly limited to its peculiar facts, as apparently did the Court itself. To the extent that it may be construed as approving federal judicial review and supervision of the exercise of prosecutorial discretion and as compelling the institution of criminal proceedings, we do not share such an extension of its views.

The order of the district court [dismissing the complaint] is affirmed.

Notes and questions on Inmates of Attica